Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Mindreading: Automaticity

Mindreading: Automaticity

s.butterfill@warwick.ac.uk & c.sinigaglia

In which domains is there substantial evidence for a two systems theory?

And what are the best objections?

How are the two systems distinguished?

What, if any, kind of unity is there across domains?

Why are there two systems?

When, if ever, are two systems better than one?

How, if at all, do the two systems interact? What are the barriers to interaction between them?

feature

‘A central characteristic of dual-process theories is that they are concerned with the question of whether the mental processes underlying social behavior operate in an automatic or nonautomatic fashion’

(Gawronski, Sherman, & Trope, 2014, p. 5)

feature

‘A central characteristic of dual-process theories is that they are concerned with the question of whether the mental processes underlying social behavior operate in an automatic or nonautomatic fashion’

(Gawronski et al., 2014, p. 5)

domain

mindreading (the process of identifying mental states and purposive actions as the mental states and purposive actions of a particular subject)

‘Maxi puts his chocolate in the BLUE box and leaves the room to play. While he is away (and cannot see), his mother moves the chocolate from the BLUE box to the GREEN box. Later Maxi returns. He wants his chocolate.’

blue

box

green box

I wonder where Maxi will look for his chocolate

‘Where will Maxi look for his chocolate?’

Wimmer & Perner 1983

Two models of minds and actions

Belief model

Fact model

Maxi wants his chocolate.

Maxi wants his chocolate.

Maxi believes his chocolate is in the blue box.

Maxi’s chocolate is in the green box.

Therefore:

Therefore:

Maxi will look in the blue box.

Maxi will look in the green box.

feature

‘A central characteristic of dual-process theories is that they are concerned with the question of whether the mental processes underlying social behavior operate in an automatic or nonautomatic fashion’

(Gawronski et al., 2014, p. 5)

domain

mindreading (the process of identifying mental states and purposive actions as the mental states and purposive actions of a particular subject)

Is adult humans’ belief-tracking automatic?

Sometimes it is not

Apperly, Back, Samson, & France, 2008; Apperly et al., 2010; Wel, Sebanz, & Knoblich, 2014

and sometimes it is

Kovács, Téglás, & Endress, 2010; Schneider, Bayliss, Becker, & Dux, 2012; Edwards & Low, 2017; Wel et al., 2014; Edwards & Low, 2019; Dana Schneider, Nott, & Dux, 2014

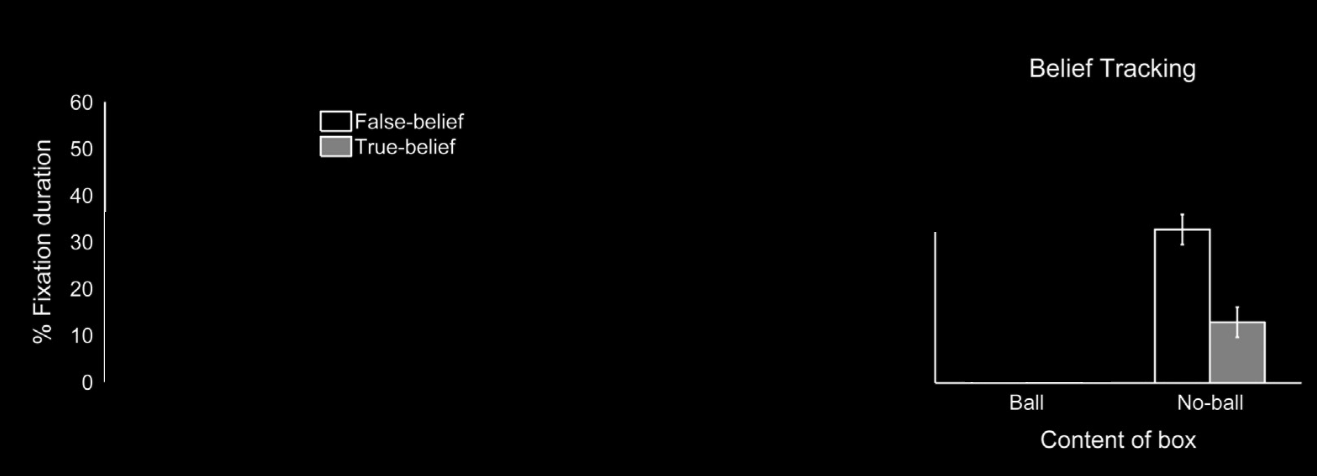

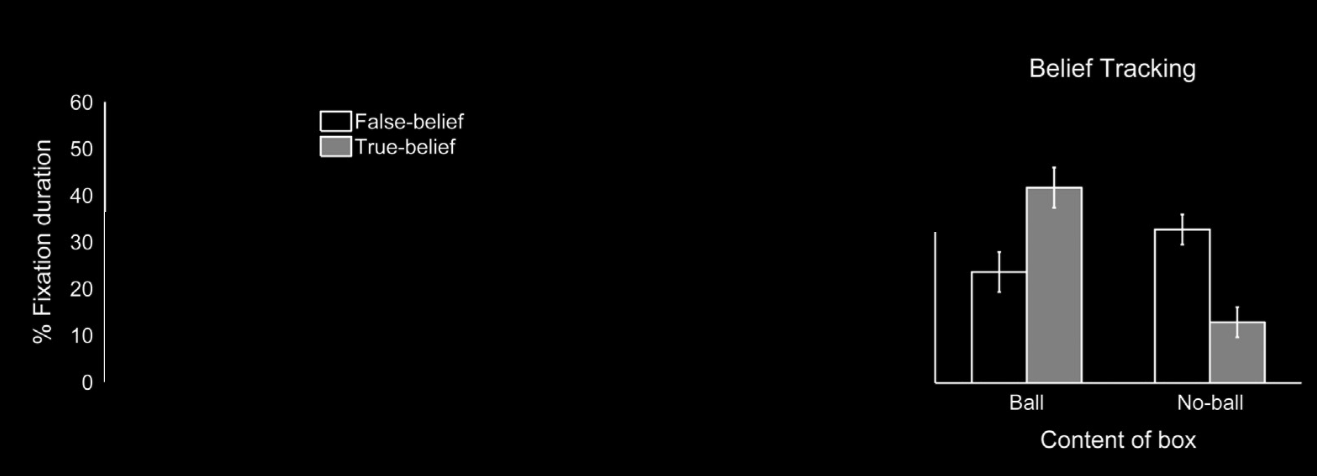

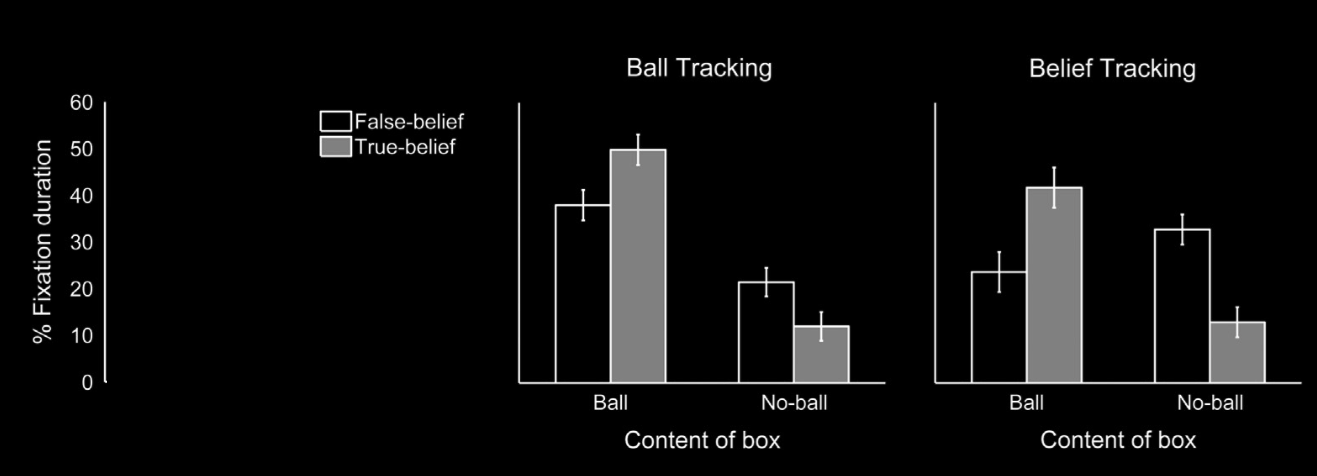

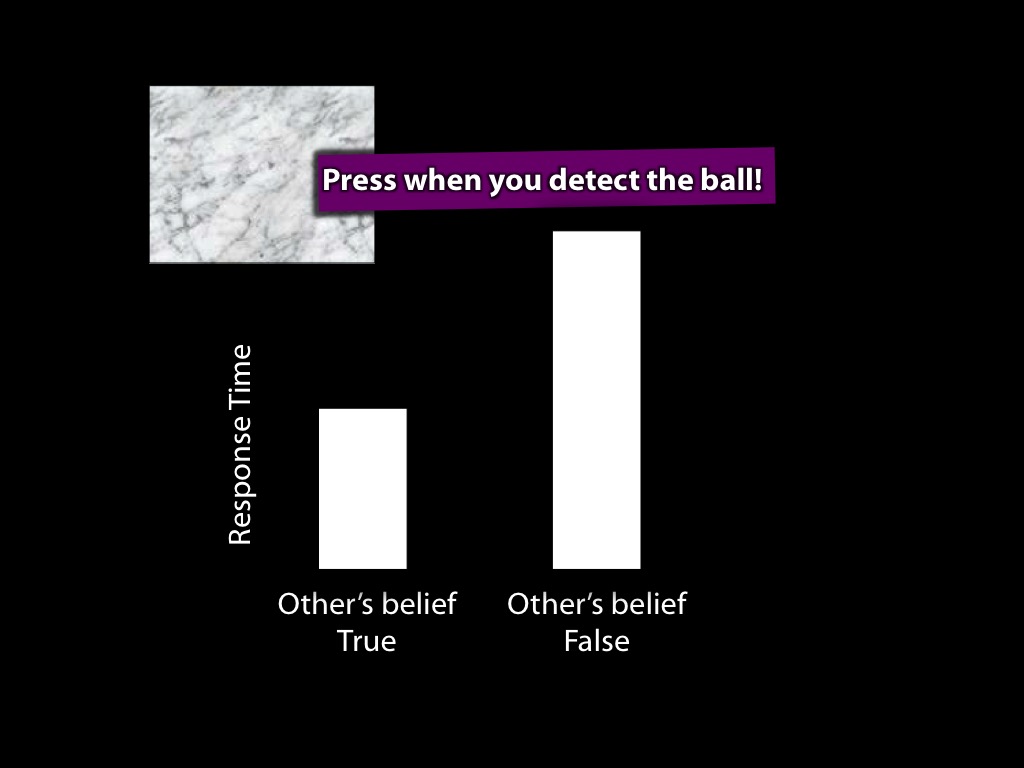

Dana Schneider et al. (2014, p. figure 1)

Dana Schneider et al. (2014, p. figure 3)

Dana Schneider et al. (2014, p. figure 3)

Dana Schneider et al. (2014, p. figure 3)

Dana Schneider et al. (2014, p. figure 3)

‘subjects … track the mental states of others even when they have instructions to complete a task that is incongruent with this operation’ (Dana Schneider et al., 2014, p. 46).

but replication (of the basic task):

- successful (Dana Schneider, Lam, Bayliss, & Dux, 2012)

- failed (Kulke, von Duhn, Schneider, & Rakoczy, 2018)

Is adult humans’ belief-tracking automatic?

Sometimes it is not

Apperly, Back, Samson, & France, 2008; Apperly et al., 2010; Wel, Sebanz, & Knoblich, 2014

and sometimes it is

Kovács, Téglás, & Endress, 2010; Schneider, Bayliss, Becker, & Dux, 2012; Edwards & Low, 2017; Wel et al., 2014; Edwards & Low, 2019; Dana Schneider, Nott, & Dux, 2014

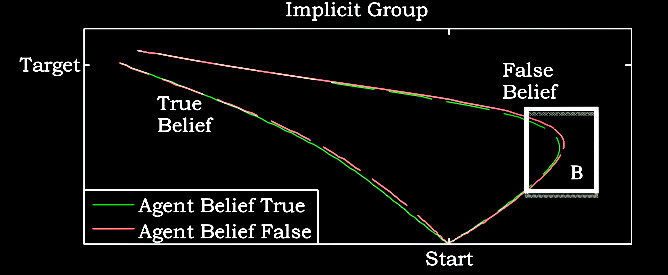

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 1)

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 2)

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 2)

Is adult humans’ belief-tracking automatic?

Sometimes it is not

Apperly, Back, Samson, & France, 2008; Apperly et al., 2010; Wel, Sebanz, & Knoblich, 2014

and sometimes it is

Kovács, Téglás, & Endress, 2010; Schneider, Bayliss, Becker, & Dux, 2012; Edwards & Low, 2017; Wel et al., 2014; Edwards & Low, 2019; Dana Schneider, Nott, & Dux, 2014

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 3)

‘they slowed down their responses when there was a belief conflict versus when there was not’

Is adult humans’ belief-tracking automatic?

Sometimes it is not

Apperly, Back, Samson, & France, 2008; Apperly et al., 2010; Wel, Sebanz, & Knoblich, 2014

and sometimes it is

Kovács, Téglás, & Endress, 2010; Schneider, Bayliss, Becker, & Dux, 2012; Edwards & Low, 2017; Wel et al., 2014; Edwards & Low, 2019; Dana Schneider, Nott, & Dux, 2014

Back & Apperly (2010, p. figure 1 (part))

Is adult humans’ belief-tracking automatic?

Sometimes it is not

Apperly, Back, Samson, & France, 2008; Apperly et al., 2010; Wel, Sebanz, & Knoblich, 2014

and sometimes it is

Kovács, Téglás, & Endress, 2010; Schneider, Bayliss, Becker, & Dux, 2012; Edwards & Low, 2017; Wel et al., 2014; Edwards & Low, 2019; Dana Schneider, Nott, & Dux, 2014

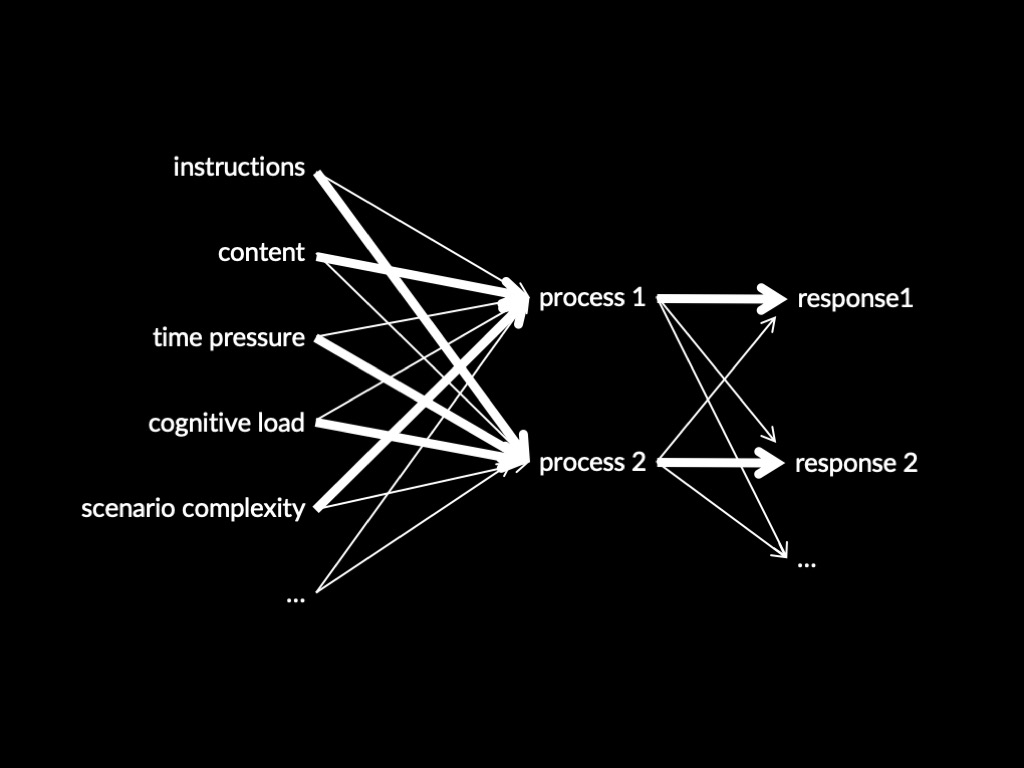

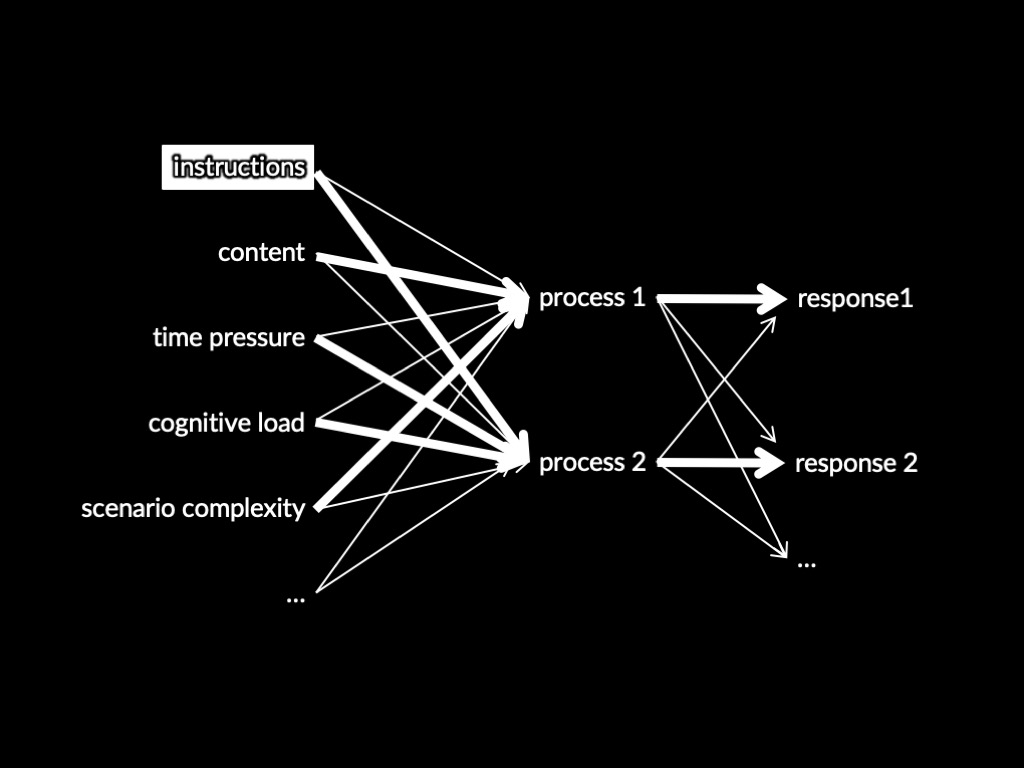

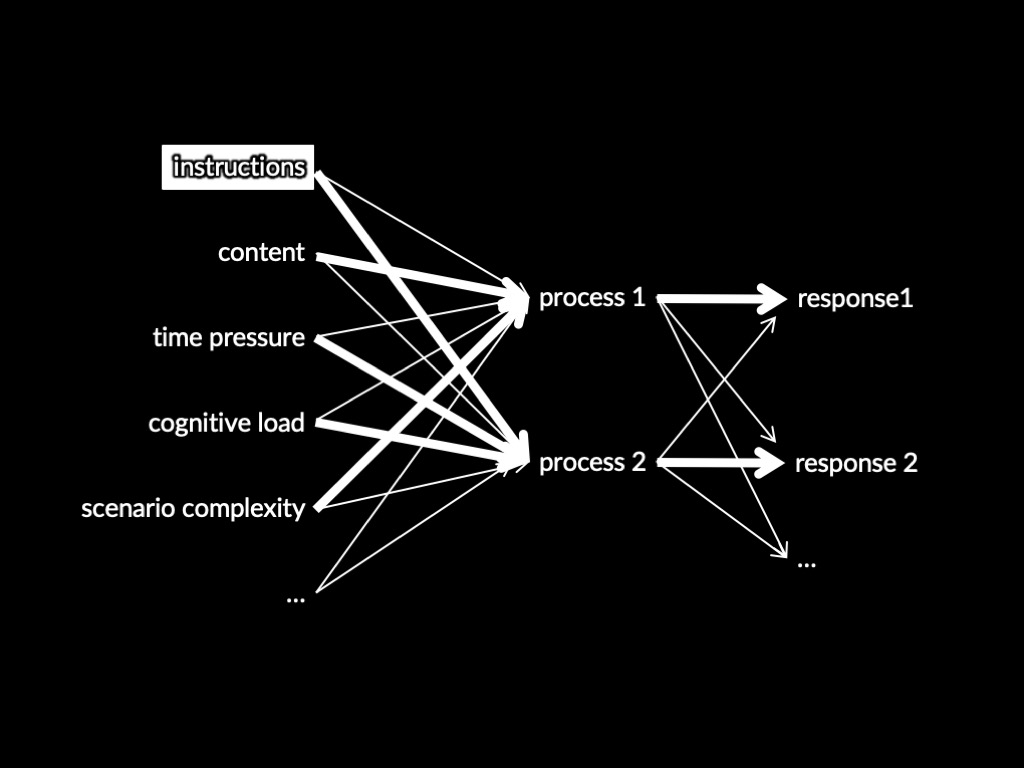

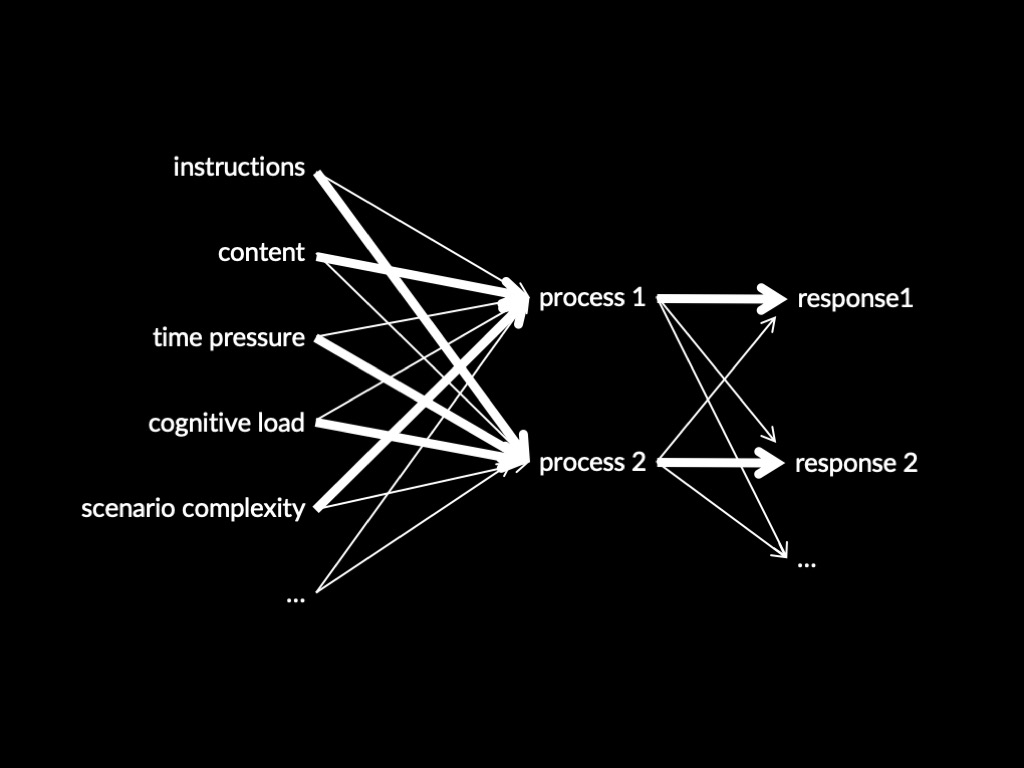

Two Systems Theory of Mindreading

Two (or more) processes concerning X are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

auxiliary hypothesis: one process is more automatic than another

In which domains is there substantial evidence for a two systems theory?

And what are the best objections?

How are the two systems distinguished?

What, if any, kind of unity is there across domains?

Why are there two systems?

When, if ever, are two systems better than one?

How, if at all, do the two systems interact? What are the barriers to interaction between them?

appendix

Kovacs et al

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010 figure 1A