Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Goal-Directed and Habitual: Some Evidence

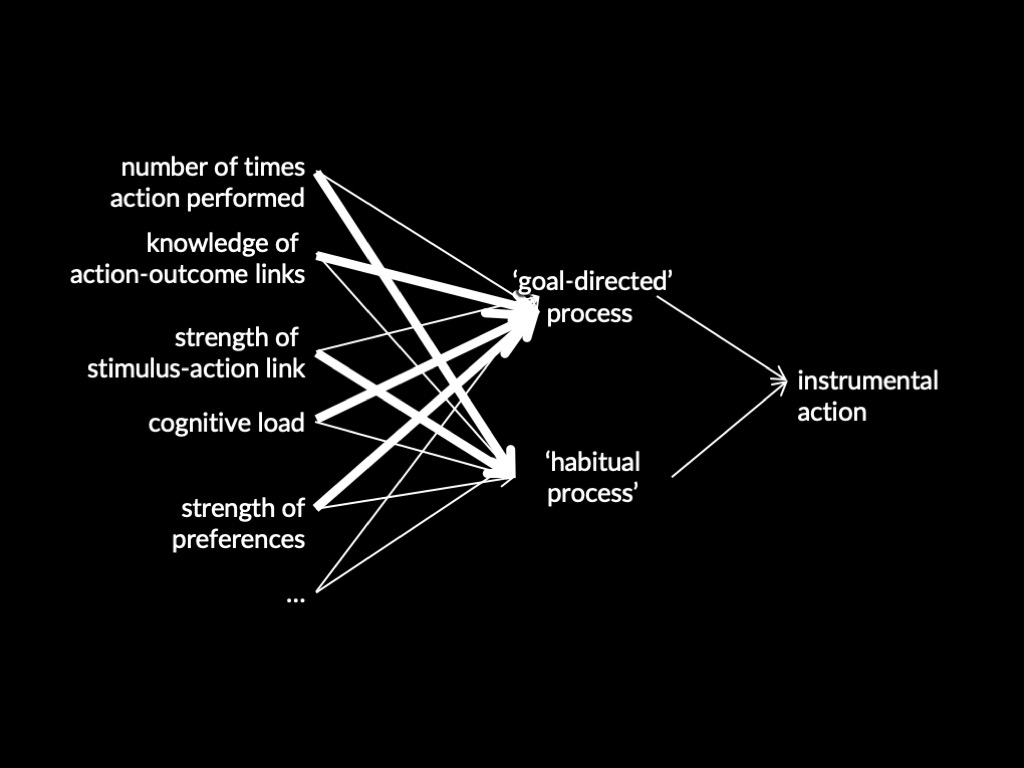

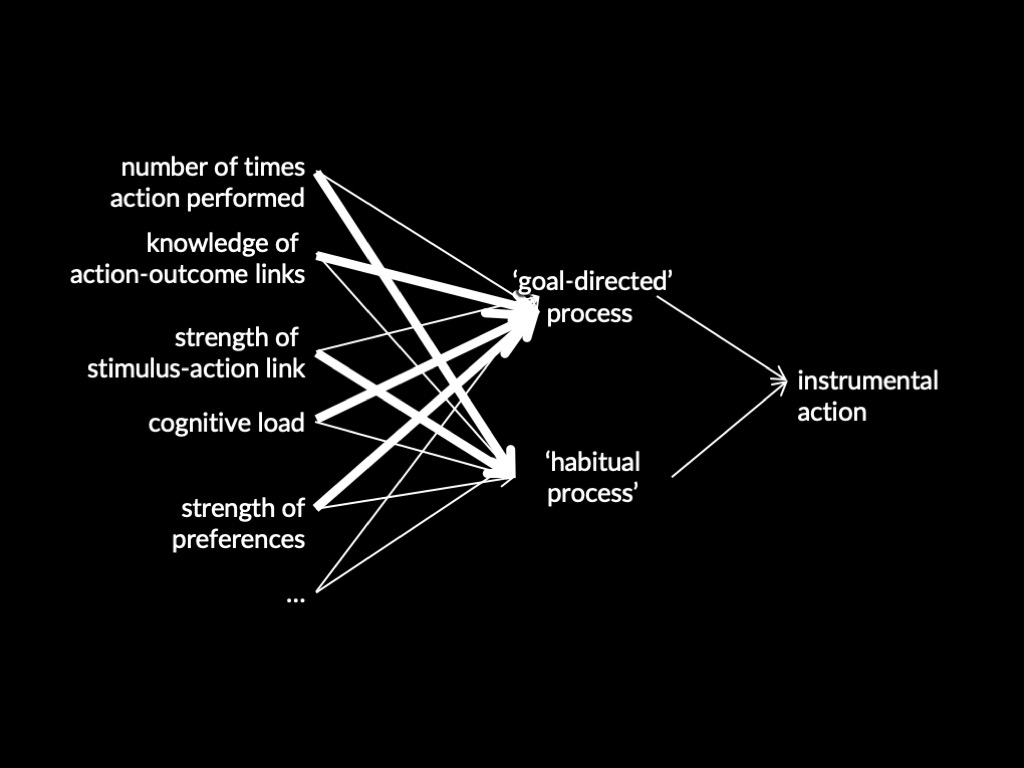

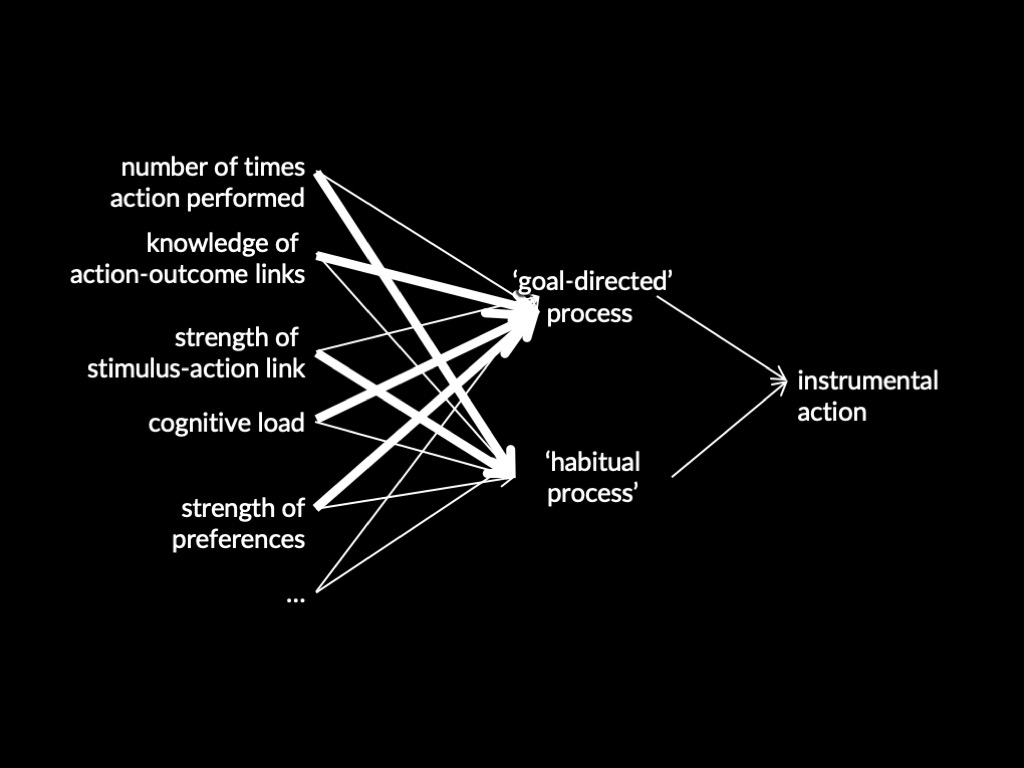

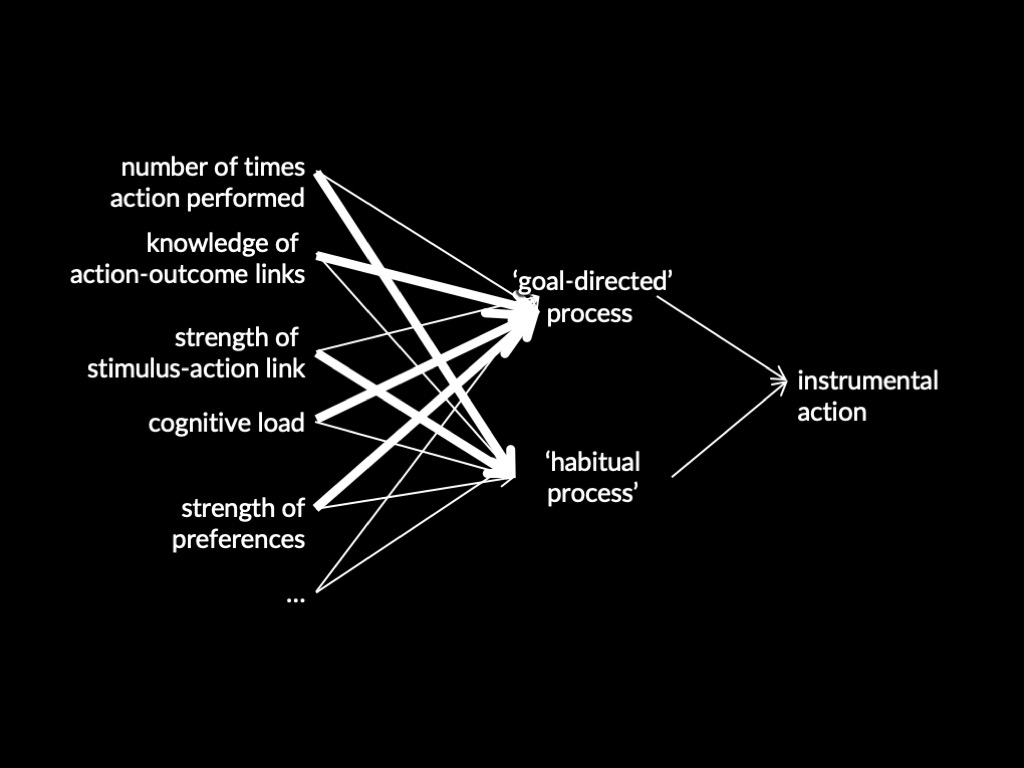

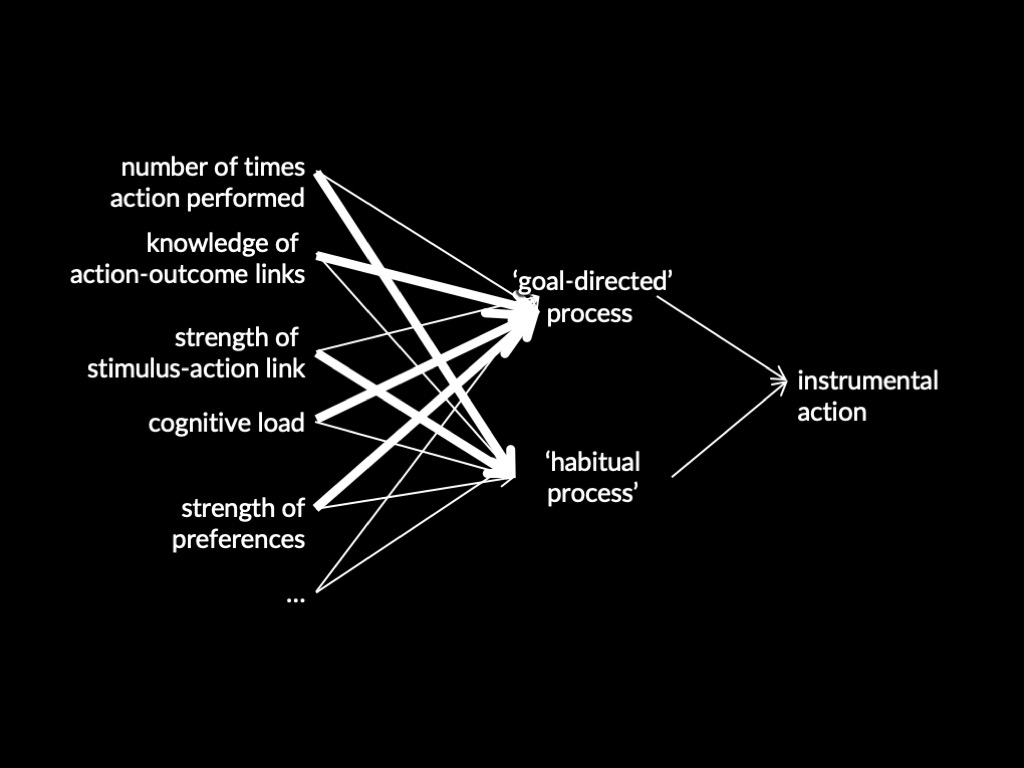

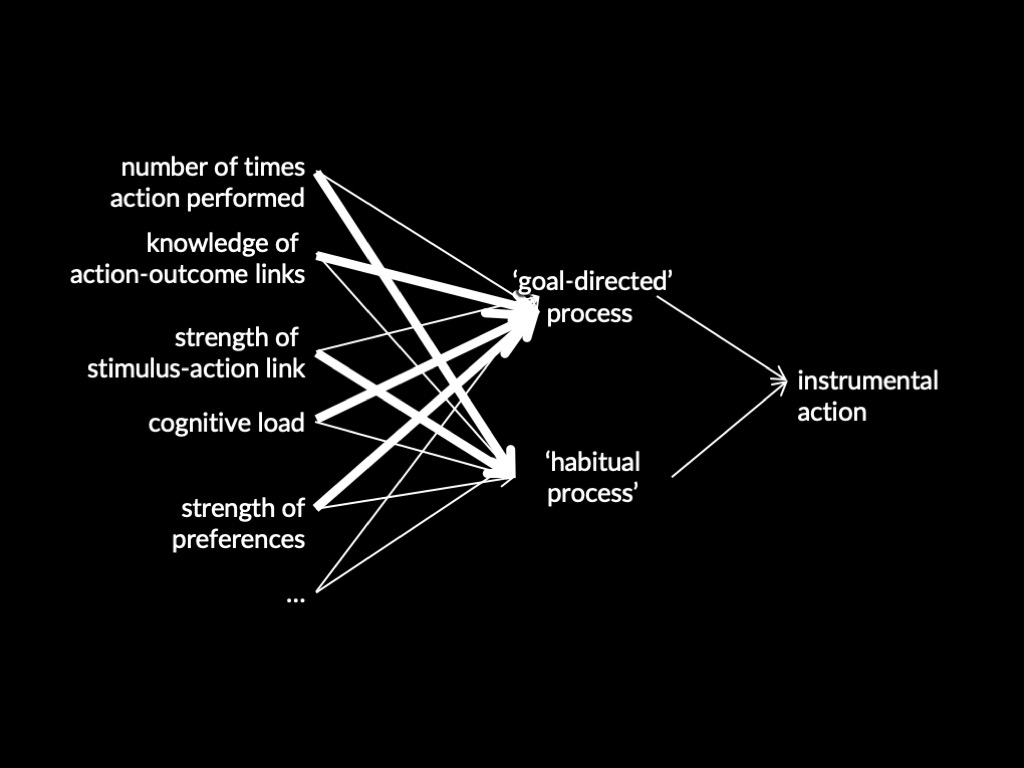

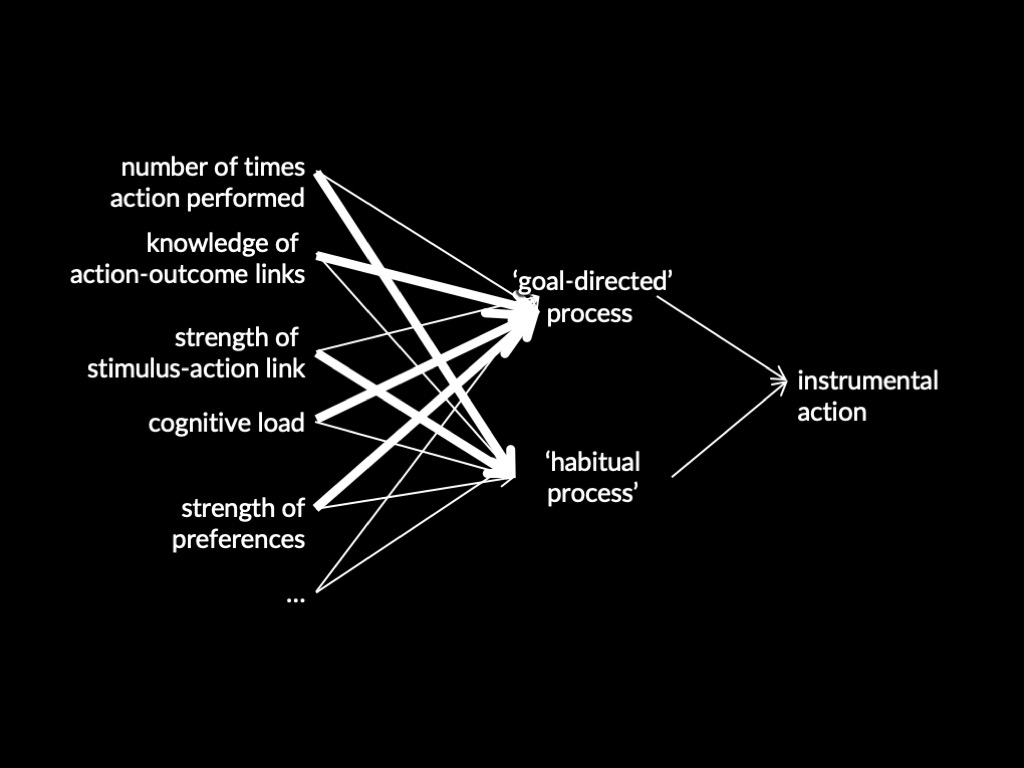

‘instrumental behavior itself involves two systems, the goal-directed and the habitual’

(Dickinson & Pérez, 2018, p. 12)

prediction?

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Agent is rewarded [/punished]

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened [/weakened] due to reward [/punishment]

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

‘instrumental behavior itself involves two systems, the goal-directed and the habitual’

(Dickinson & Pérez, 2018, p. 12)

prediction?

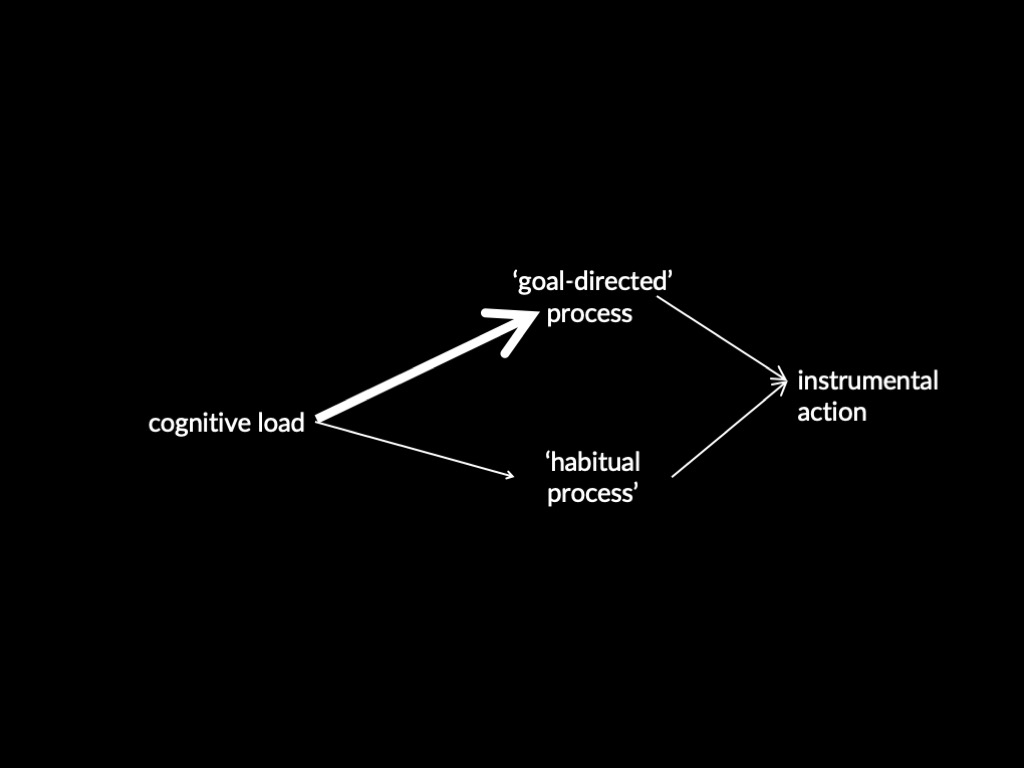

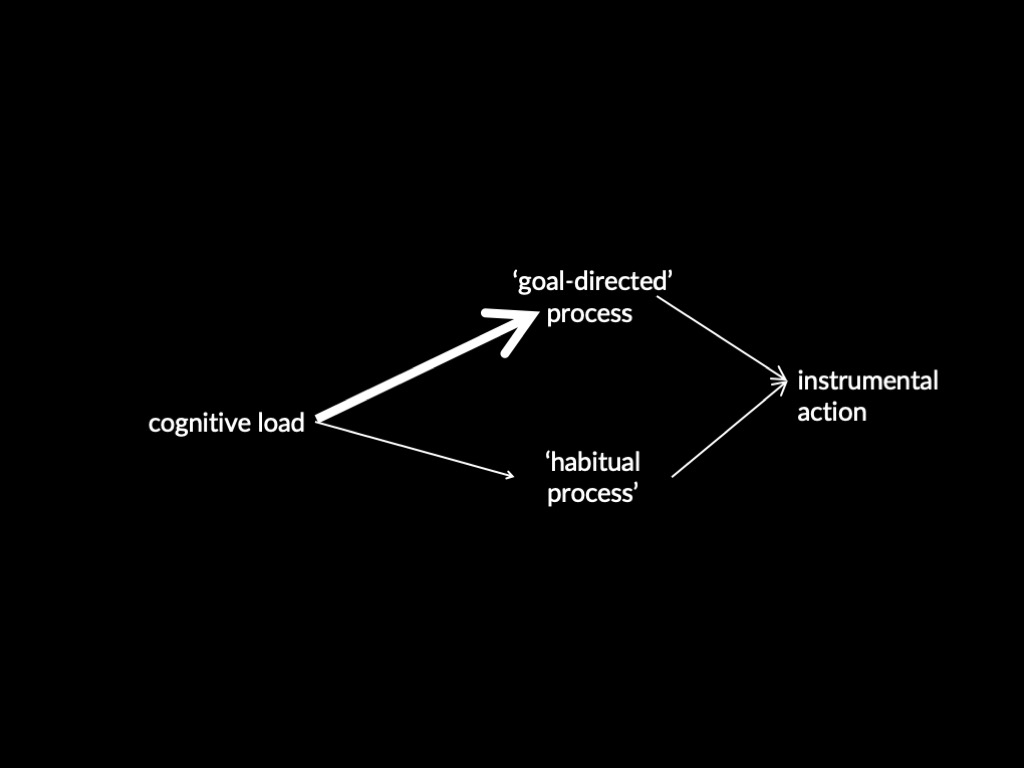

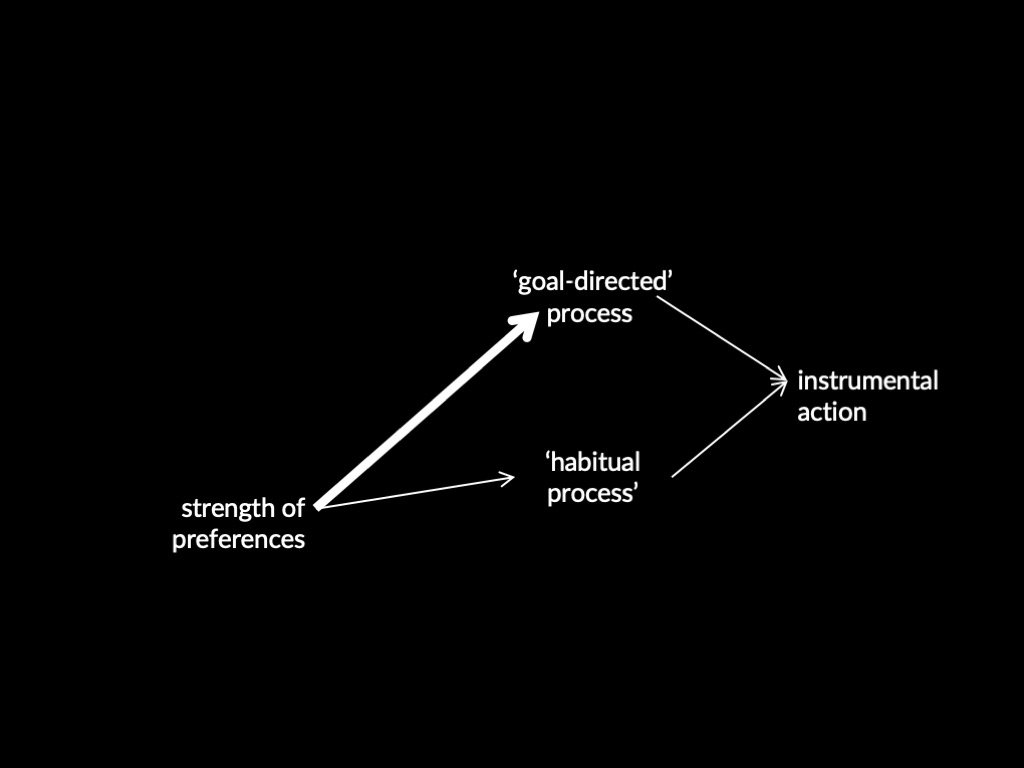

prediction: increasing stress will reduce the influence of your preferences

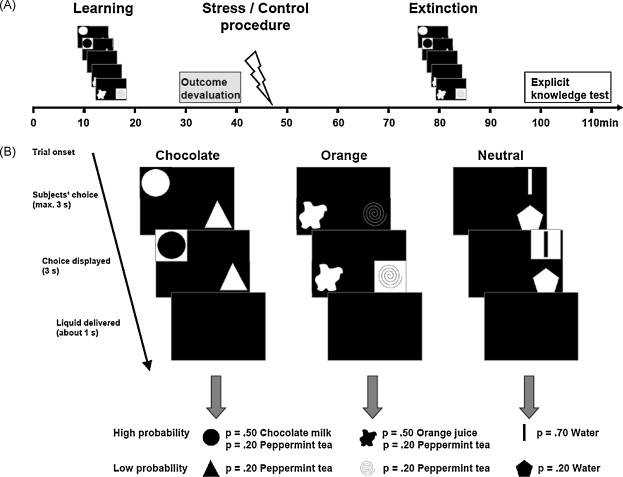

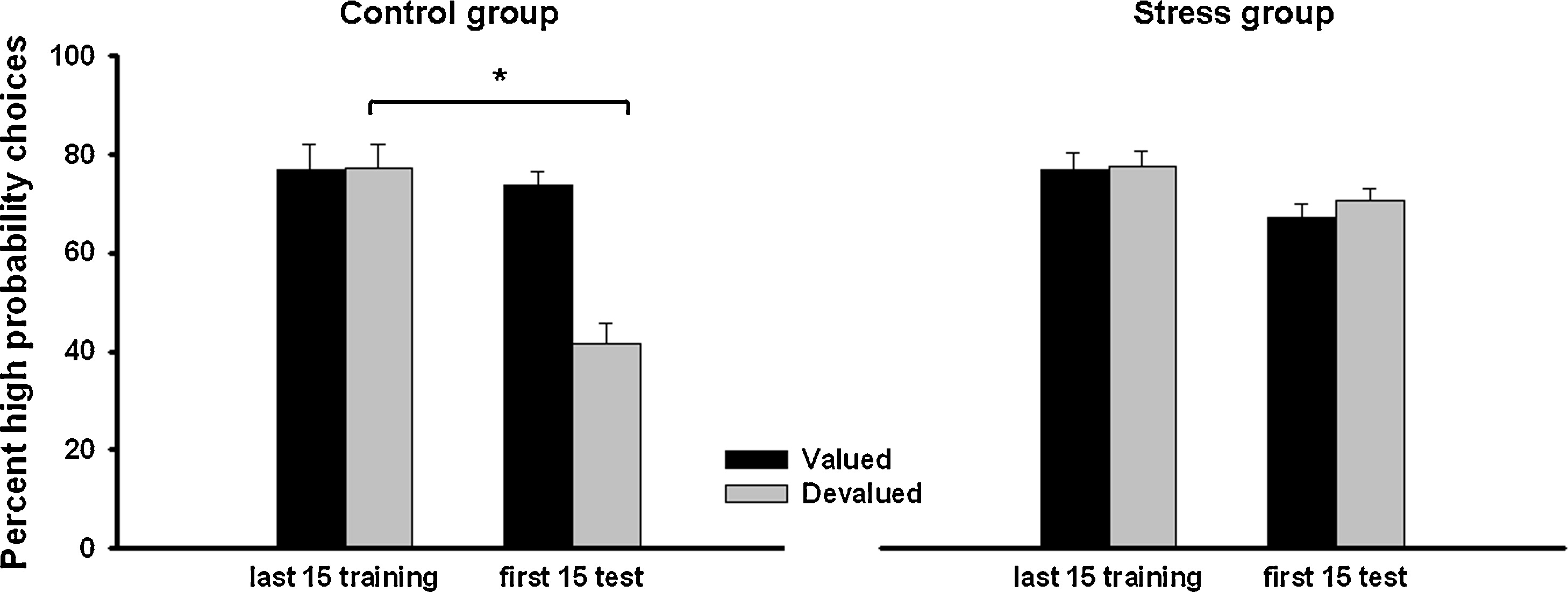

Evidence: Schwabe & Wolf, 2010

Schwabe and Wolf, 2010 figure 1

Schwabe and Wolf, 2010 figure 6

When stressed,

your preferences matter less:

habits dominate.

How is this evidence for the dual-process theory of instrumental action?

more evidence

training effects

background: goal-directed processes in young children

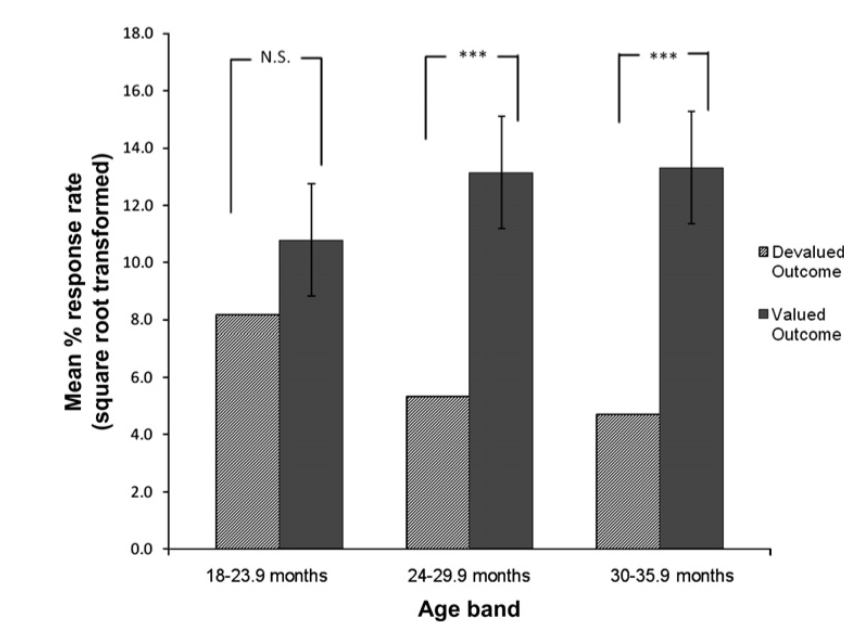

Klossek & Dickinson, 2012 figure 1a

Klossek & Dickinson, 2012 figure 2

Why is this evidence of goal-directed processes in the older age groups?

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Agent is rewarded [/punished]

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened [/weakened] due to reward [/punishment]

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

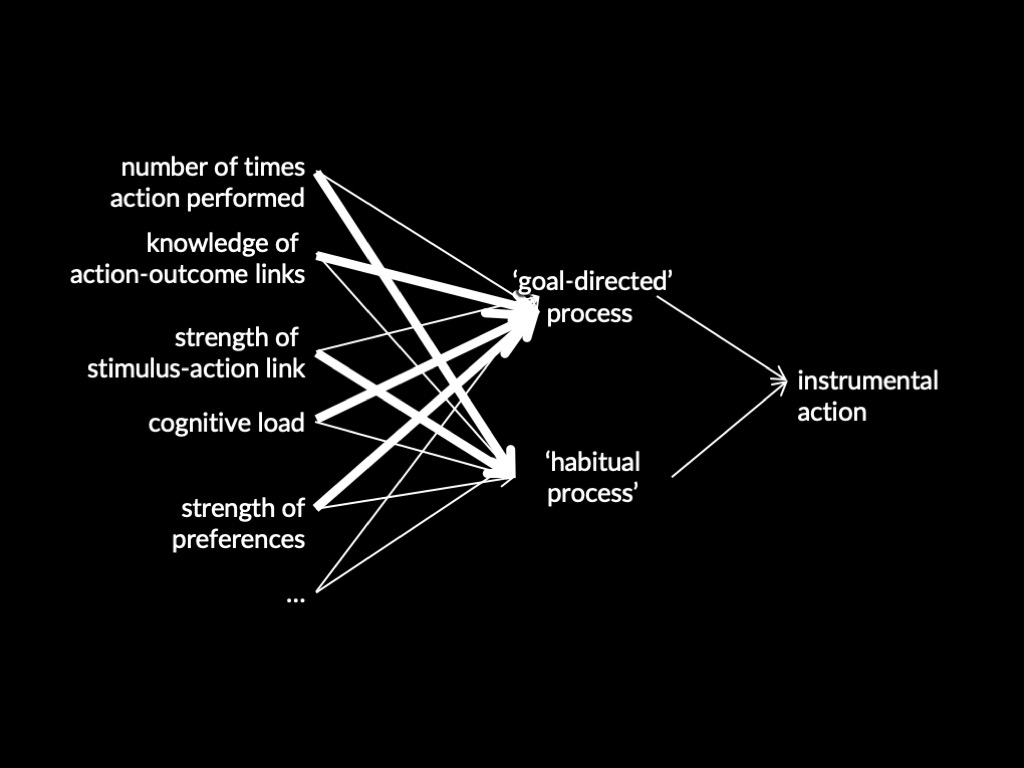

Where is the evidence for the dual-process theory of instrumental action?

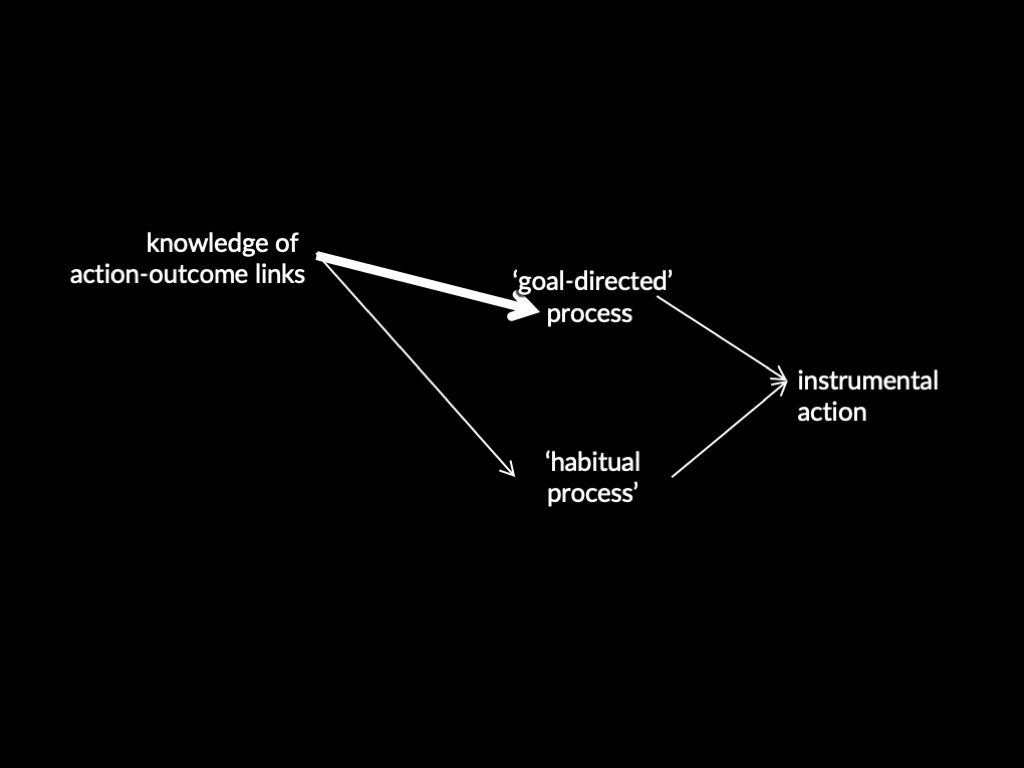

What happens if we train people with just one action possibility (rather than two)?

premise:

‘Once responding at a high and constant rate in the single-action condition after extended training, agents no longer experience [...] episodes in which they do not respond and do not receive the outcome. As a result, the action-outcome causal representation necessary for goal-directed action is not maintained.’

(Dickinson, 2016, p. 181)

prediction: devaluation will have less effect in one- than in two-action-training

(because habitual processes will be more influential in one- than in two-action-training )

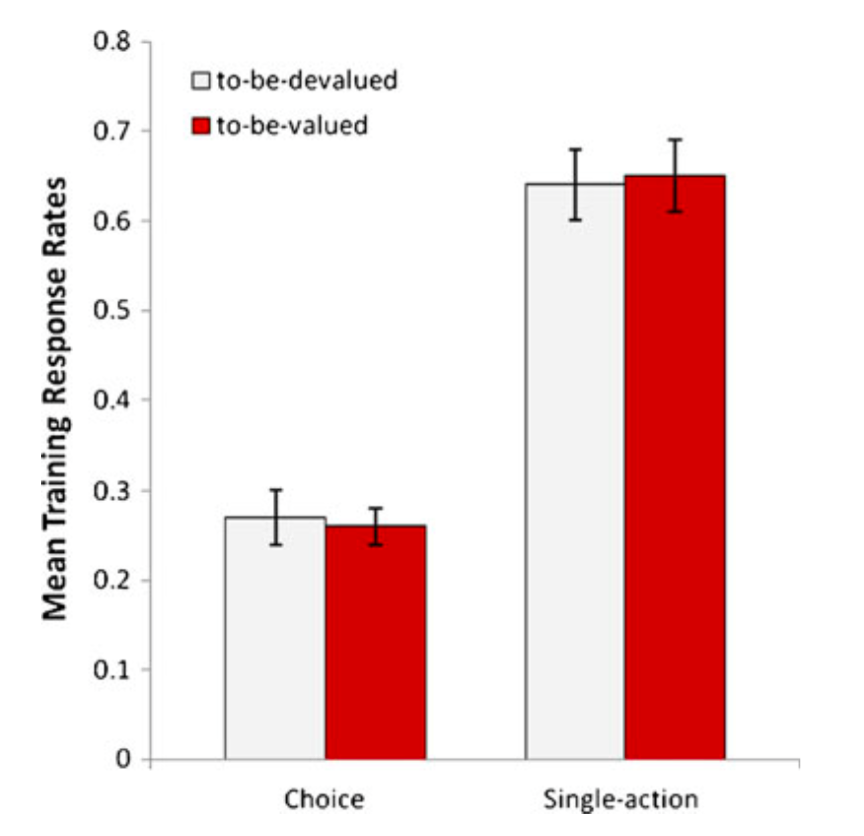

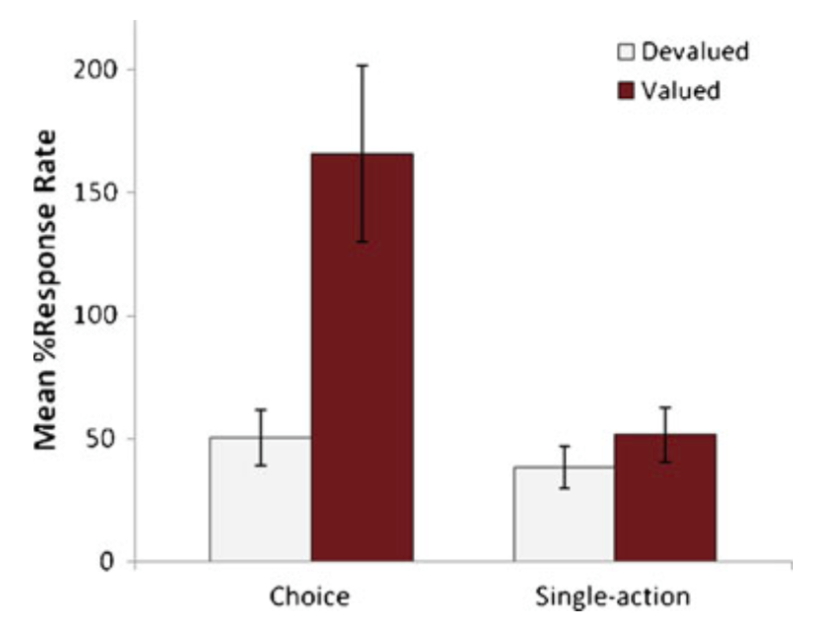

Training Effects (Klossek, Yu & Dickinson, 2011)

Subjects: 3-4 year olds

Training:

Choice Group : perform Action1 to see Clip1 or Action2 to see Clip2

Single-Action Group : only one action is available at once

(Frequency of Action1 and Action2 is matched across groups!)

Devalue Clip1 (expose to satiety)

Test: both actions available. What do Ss select?

Results:

Choice group selects Action2

Single-Action Group selects Action1 and Action2 equally

Klossek et al, 2011 figure 1

Klossek et al, 2011 figure 2

Whether you learn about the effects of an action

can influence

whether that action becomes dominated by instrumental or habitual processes.

Why is this evidence for the dual-process theory of instrumental action?

What happens if we train people with just one action possibility (rather than two)?

premise:

‘Once responding at a high and constant rate in the single-action condition after extended training, agents no longer experience [...] episodes in which they do not respond and do not receive the outcome. As a result, the action-outcome causal representation necessary for goal-directed action is not maintained.’

(Dickinson, 2016, p. 181)

prediction: devaluation will have less effect in one- than in two-action-training

(because habitual processes will be more influential in one- than in two-action-training )

more evidence

neurophysiology

‘[instumental] and habitual control have been doubly dissociated in two brain regions.

In the PFC, lesions of the prelimbic and infralimbic areas disrupt goal-directed and habitual behavior, respectively ...

These dissociations suggest that different neural circuits mediate the two forms of control’

Dickinson, 2016 p. 184

conclusion - three bits of evidence

- cognitive load (via stress) - Schwabe & Wolf (2010)

- representation of contingency - Klossek, Yu, & Dickinson (2011)

- neurophysiology - Dickinson (2016)