Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Ethics: Significance of Two Systems

Ethics: Significance of Two Systems

s.butterfill@warwick.ac.uk & c.sinigaglia

not-justified-inferentially premises

‘Intuition is a resource in all of philosophy, but perhaps nowhere more than in ethics’

(Audi, 2015, p. 57).

‘Episodic intuitions [...] can serve as data [...] beliefs that derive from them receive prima facie justification’ (p. 65).

not-justified-inferentially premises:

an illustration

‘Chidi is the driver of a trolley, whose brakes have just failed. [...] Chidi can turn the trolley, killing the one; or he can refrain from turning the trolley, killing the five’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 206).

May Chidi turn the trolley?

Why may Chidi but not Eleanor?

Foot (1967): because duties not to harm rank above duties to help

Why may Frank but not Eleanor?

Thomson’s argument

If Foot, then Frank may not.

But Frank may.

Therefore: not Foot.

‘Eleanor can take the healthy specimen's parts, killing him, and install them in his [five] patients, saving them. Or he can refrain from taking the healthy specimen's parts, letting his [five] patients die’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 206).

May Eleanor kill the healthy person?

‘Frank is a passenger on a trolley whose driver has just shouted that the trolley's brakes have failed, and who then died of the shock. [...] Frank can turn the trolley, killing the one; or he can refrain from turning the trolley, letting the five die’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 207).

May Frank turn the trolley?

Thomson’s proposal

‘what matters [...] is whether the agent distributes it by doing something to it, or whether he distributes it by doing something to a person’

(Thomson, 1976, p. 216).

‘Frank is a passenger on a trolley whose driver has just shouted that the trolley's brakes have failed, and who then died of the shock. [...] Frank can turn the trolley, killing the one; or he can refrain from turning the trolley, letting the five die’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 207).

May Frank turn the trolley?

‘Eleanor can take the healthy specimen's parts, killing him, and install them in his [five] patients, saving them. Or he can refrain from taking the healthy specimen's parts, letting his [five] patients die’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 206).

May Eleanor kill the healthy person?

so far:

Some ethical arguments are driven by intuition.

Greene’s Argument

a loose reconstruction, avoiding premises about which factors are morally relevant.

1. Fast processes influence which intutions you have.

2. Fast processes are limited.

Therefore:

3. Where an ethical argument for a conclusion over which humans divide relies on intuitions as premises, we cannot use the argument to gain knowledge of its conclusion.

McCloskey, Caramazza, & Green (1980, p. figure 2D)

why?

because fast processes make it appear so

(Kozhevnikov & Hegarty, 2001)

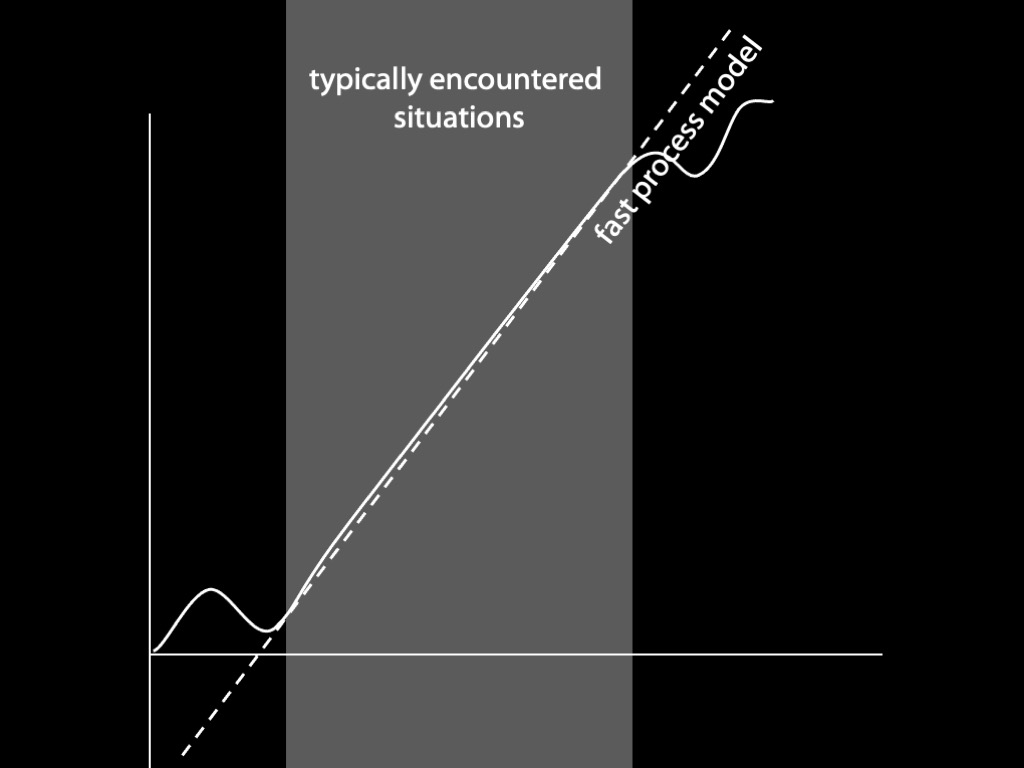

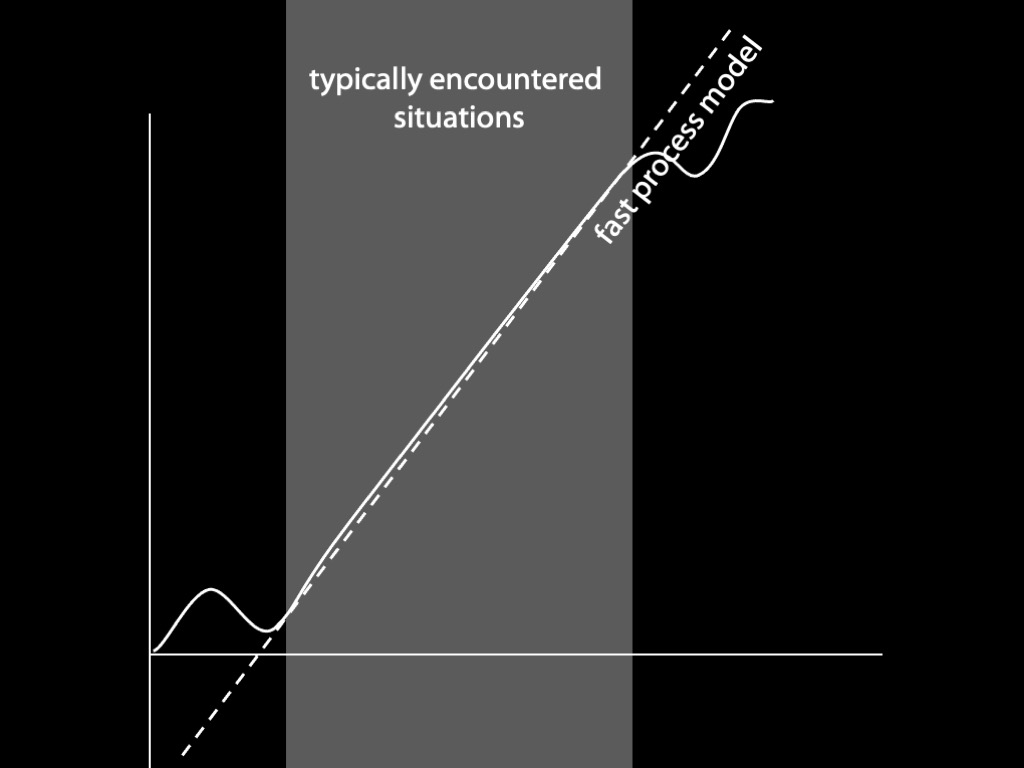

Does the fast process directly influence the slow judgement?

No. (Or not significantly.)

fast process -> appearance + high subjective confidence

reflection on appearance -> slow judgement

The fast process provides phenomenal material for slow judgement.

Fast processes influence physical intuitions. Can we infer that they also influence moral intuitions?

(What other factors might influence moral intuitions?)

1. Fast processes influence which intutions you have.

2. Fast processes are limited.

Therefore:

3. Where an ethical argument for a conclusion over which humans divide relies on intuitions as premises, we cannot use the argument to gain knowledge of its conclusion.

Can we expect to find limits?

Fast processes are flexible and trainable. (No mention of limits.)

Railton (2014)

In other domains, fast processes show signature limits even in expert adults

- Objects (Kozhevnikov & Hegarty, 2001)

- Minds (Low, Apperly, Butterfill, & Rakoczy, 2016)

- Number (Feigenson, Dehaene, & Spelke, 2004)

This is not an accident: any broadly inferential process must make a trade-off between speed and accuracy.

wicked learning environments

‘When a person’s past experience is both representative of the situation relevant to the decision and supported by much valid feedback, trust the intuition; when it is not, be careful’

(Hogarth, 2010, p. 343).

action at a distance

weapons of mass destruction (Thomson, 1976)

...

1. Fast processes influence which intutions you have.

2. Fast processes are limited.

Therefore:

3. Where an ethical argument for a conclusion over which humans divide relies on intuitions as premises, we cannot use the argument to gain knowledge of its conclusion.

application: reflective equilibrium

‘one may think of physical moral theory at first [...]

as the attempt to describe our moralperceptual capacity

[...]

what is required is

a formulation of a set of principles which,

when conjoined to our beliefs and knowledge of the circumstances,

would lead us to make these judgments with their supporting reasons

were we to apply these principles’

Rawls, 1999 p. 41

Dilemma for Rawls’ Reflective Equilibrium

Horn 1 : If you include not-justified-inferentially judgements about, or with implications for, unfamiliar* situations, you are not justified in starting there.

Horn 2 : If you include only not-justified-inferentially judgements about familiar* situations, you are not justified in generalising from them.

1. Fast processes influence which intutions you have.

2. Fast processes are limited.

Therefore:

3. Where an ethical argument for a conclusion over which humans divide relies on intuitions as premises, we cannot use the argument to gain knowledge of its conclusion.