Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Ethical Cognition

Ethical Cognition

s.butterfill@warwick.ac.uk & c.sinigaglia

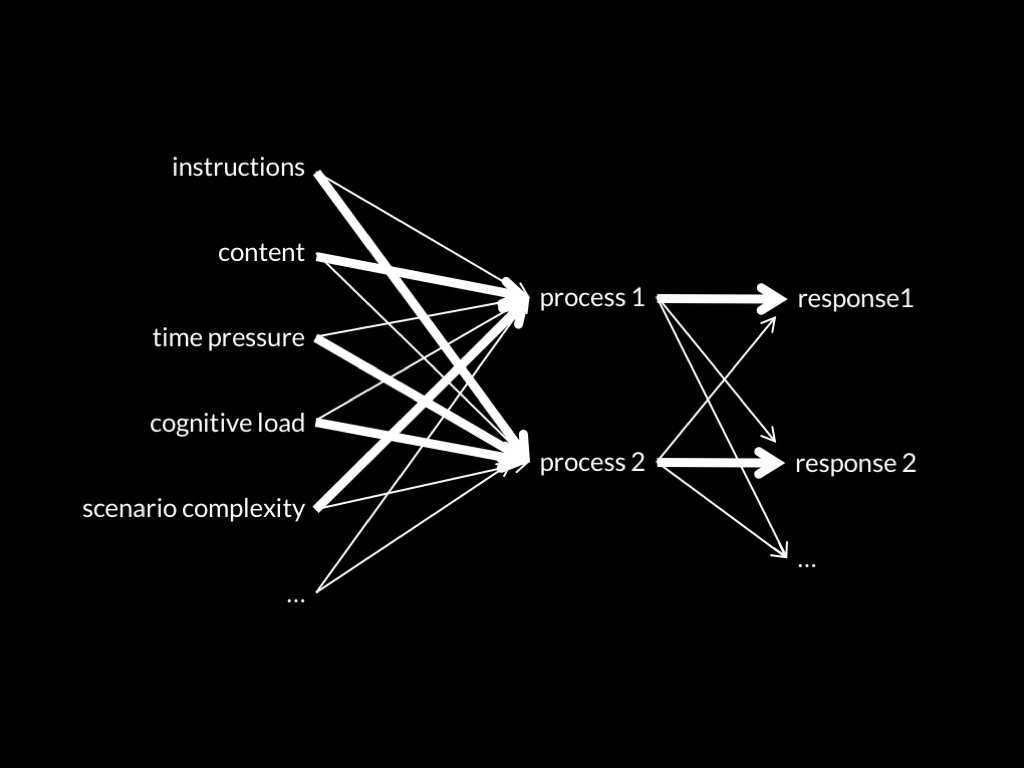

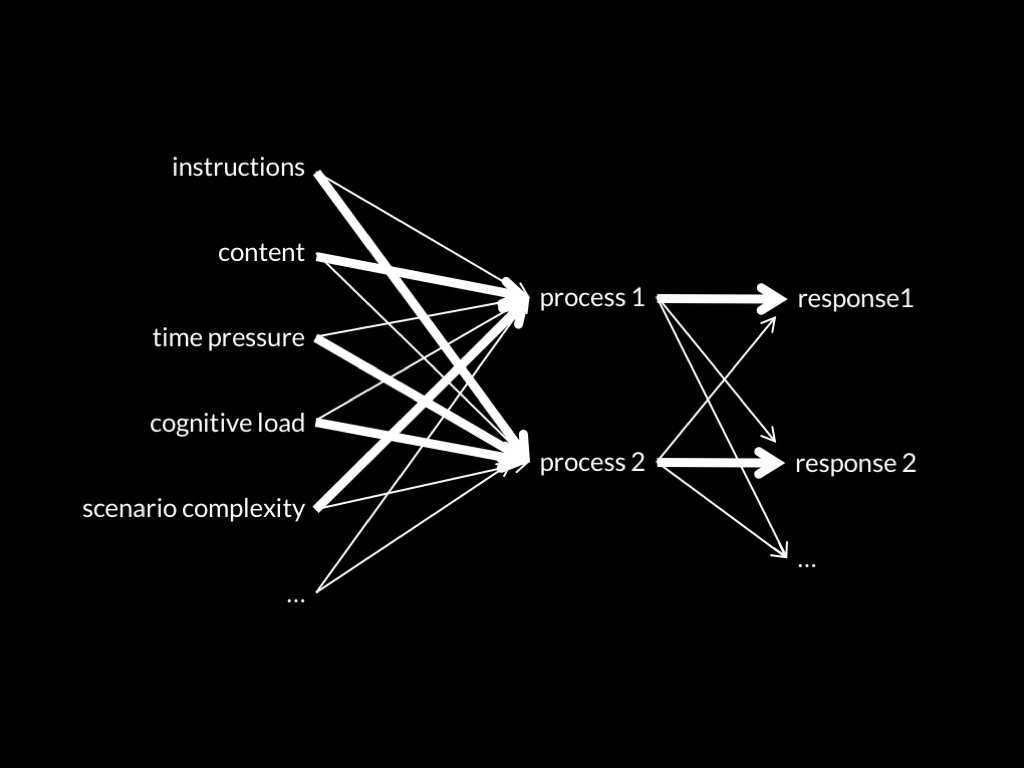

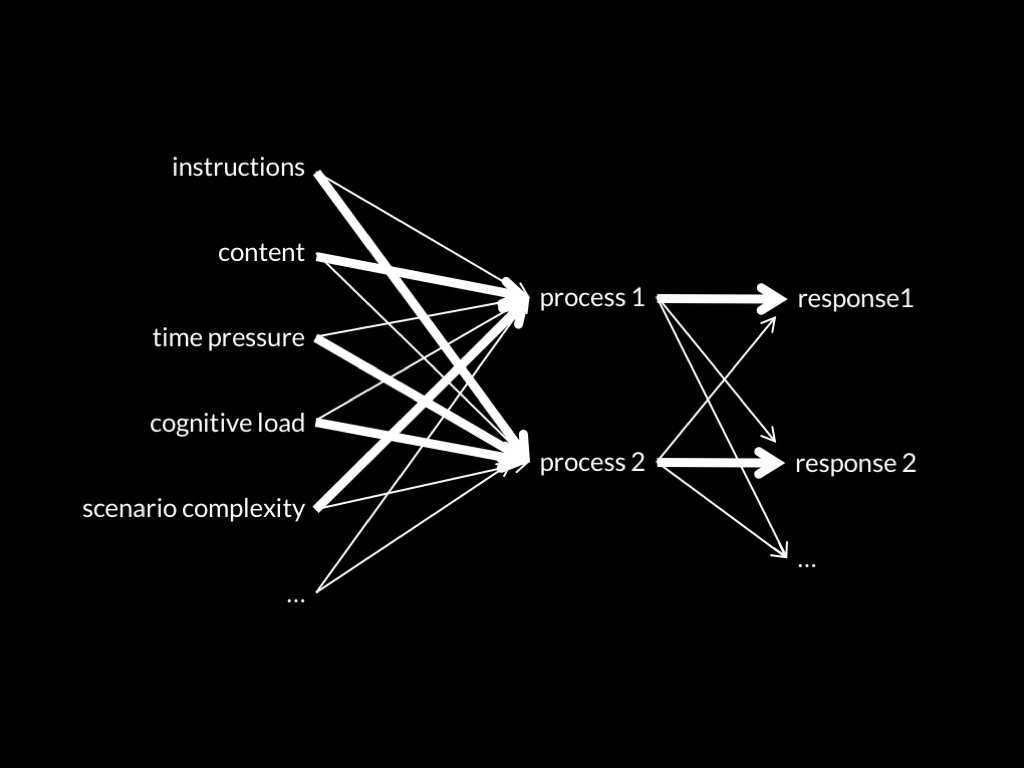

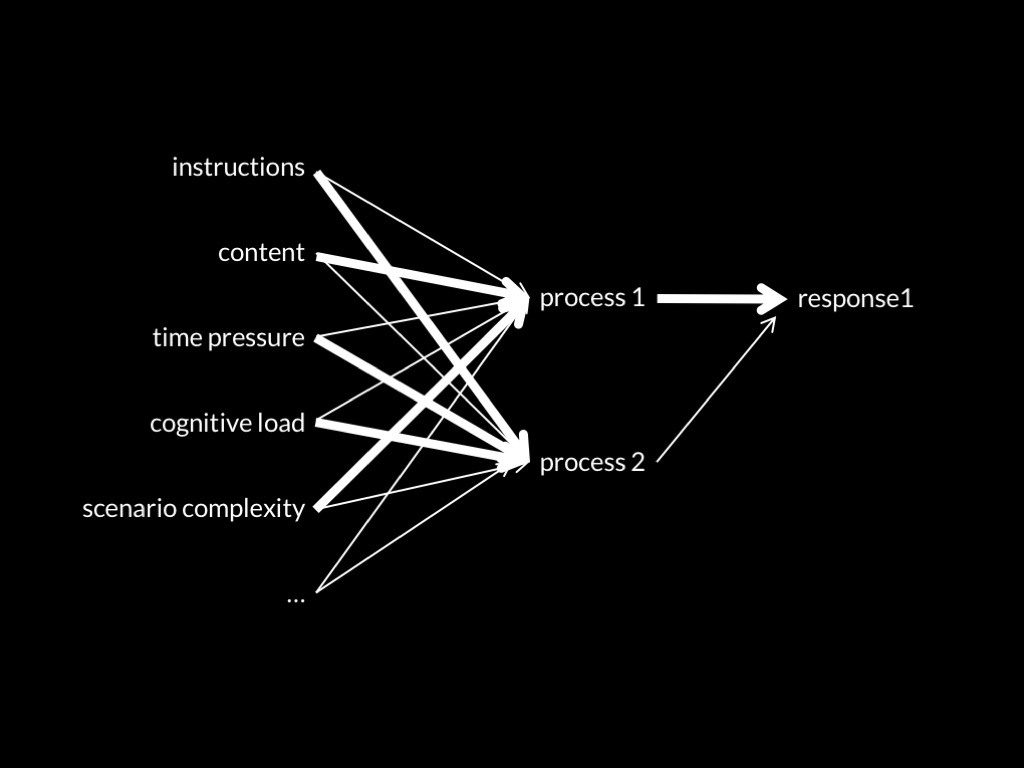

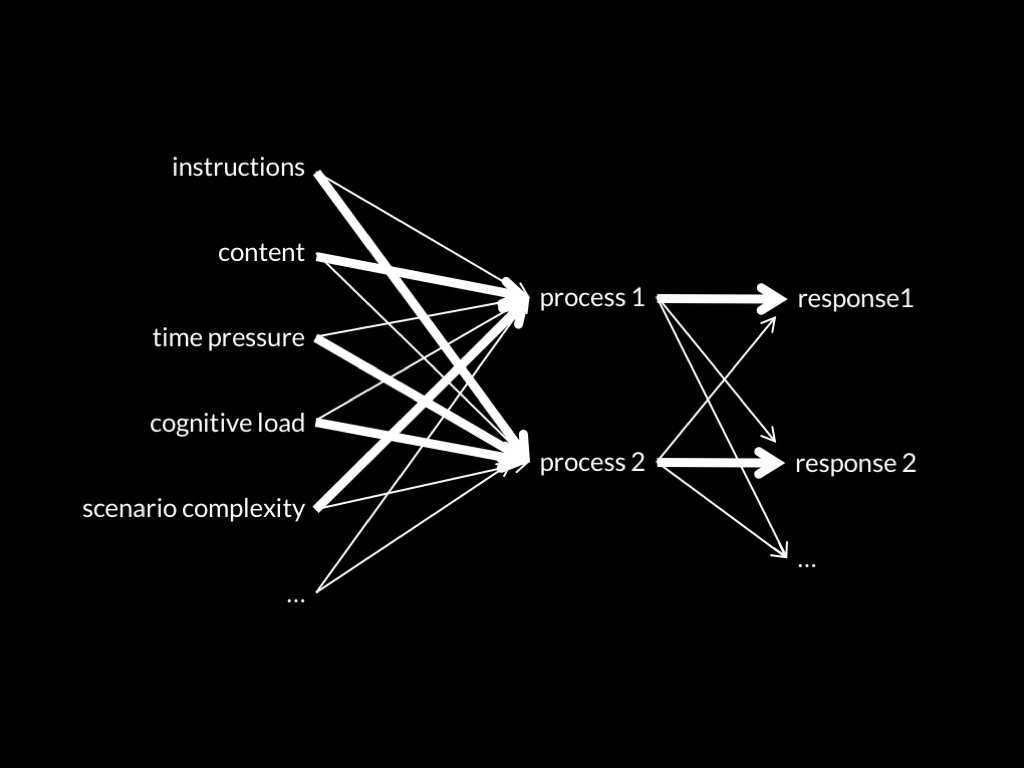

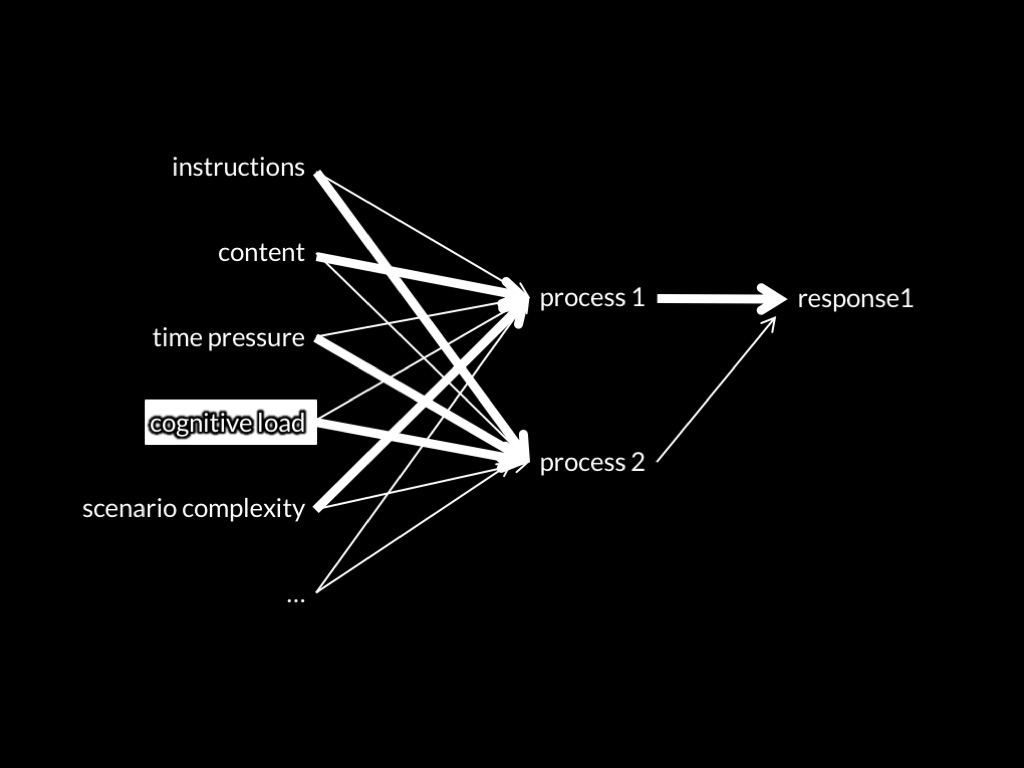

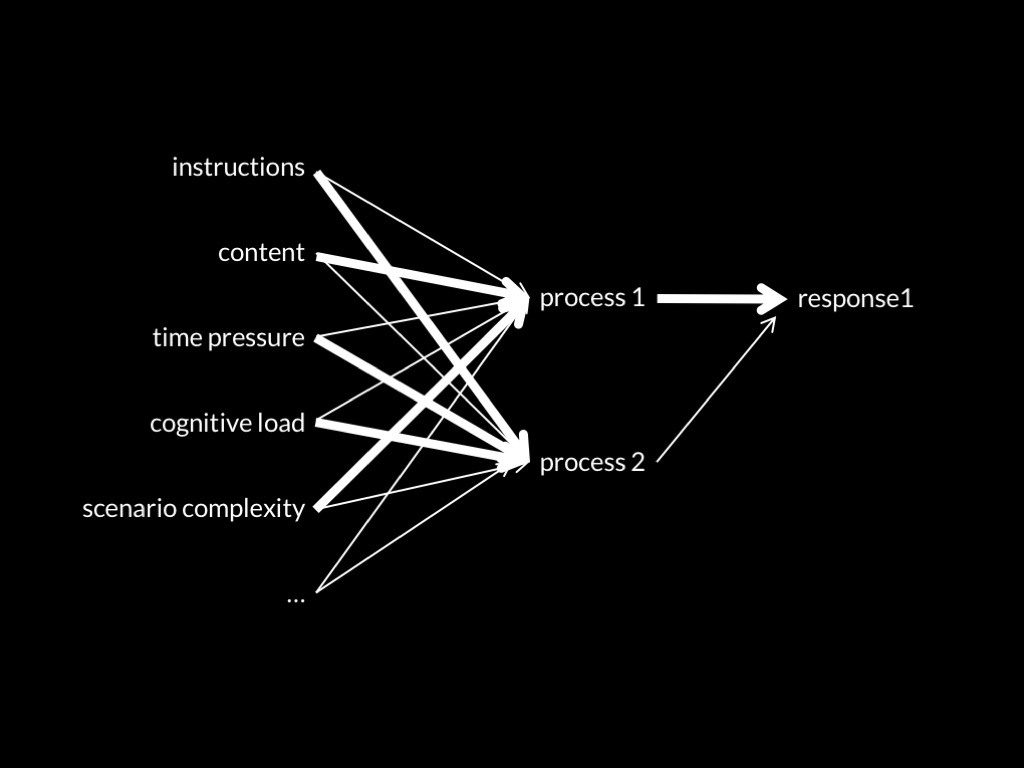

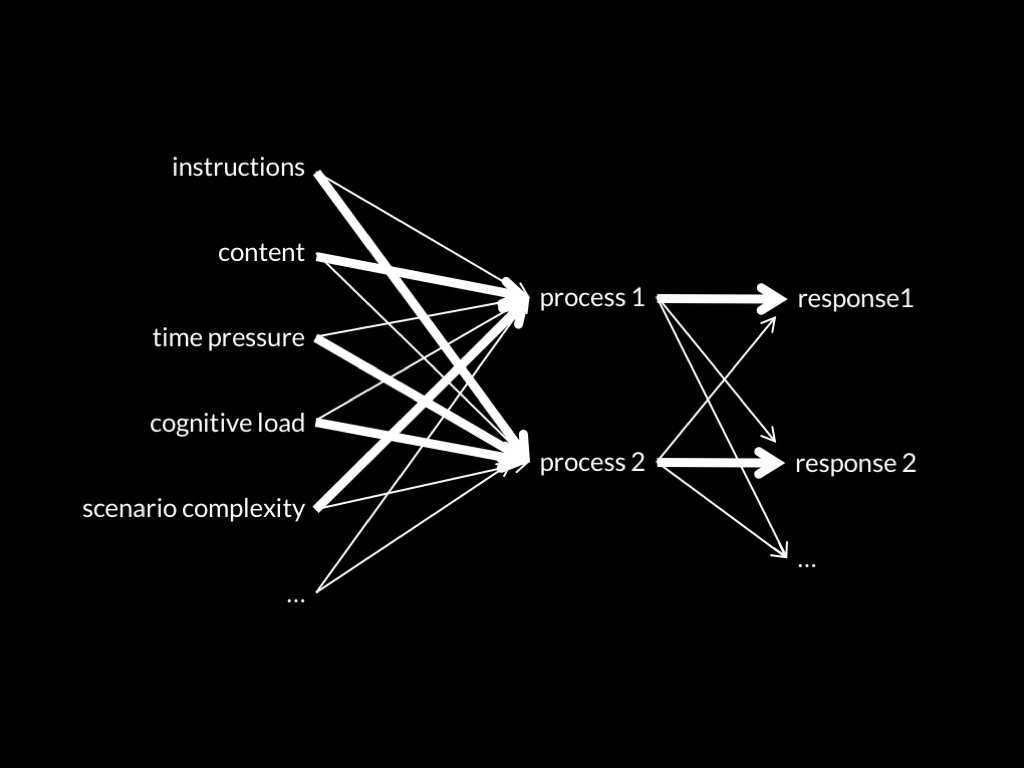

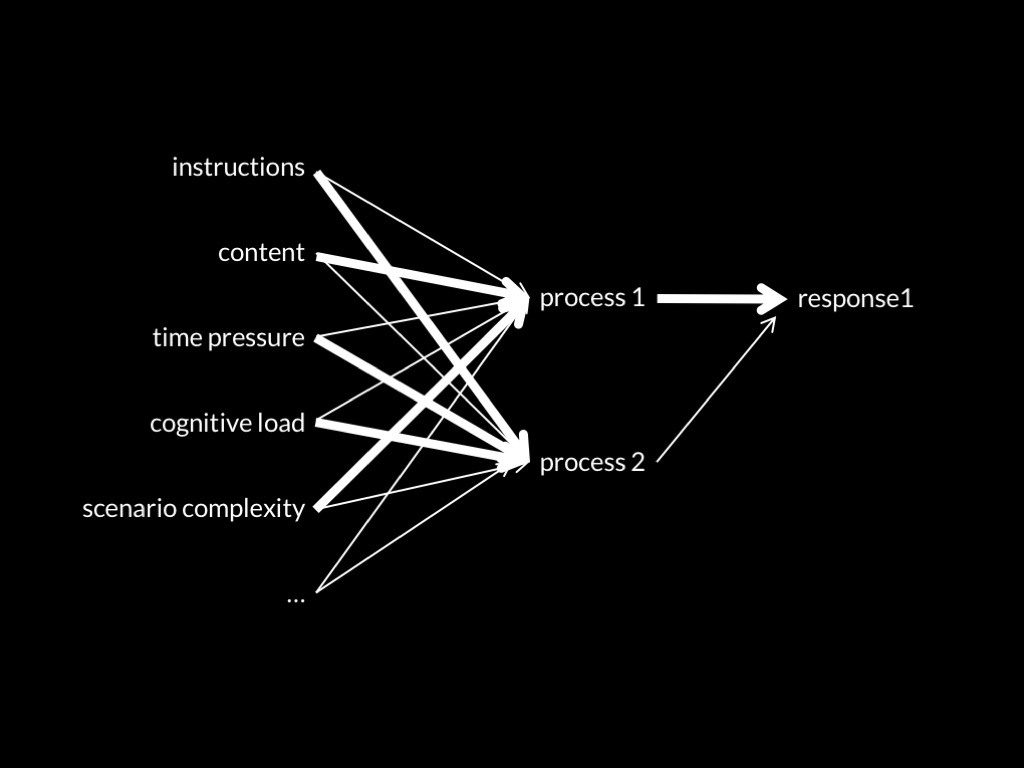

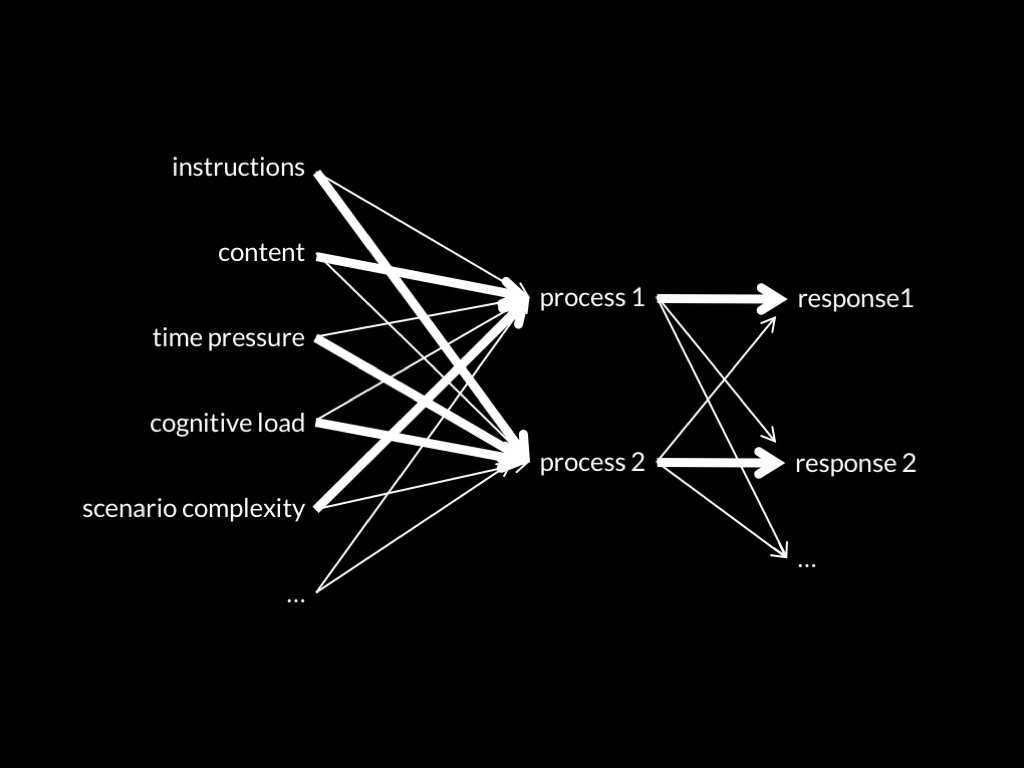

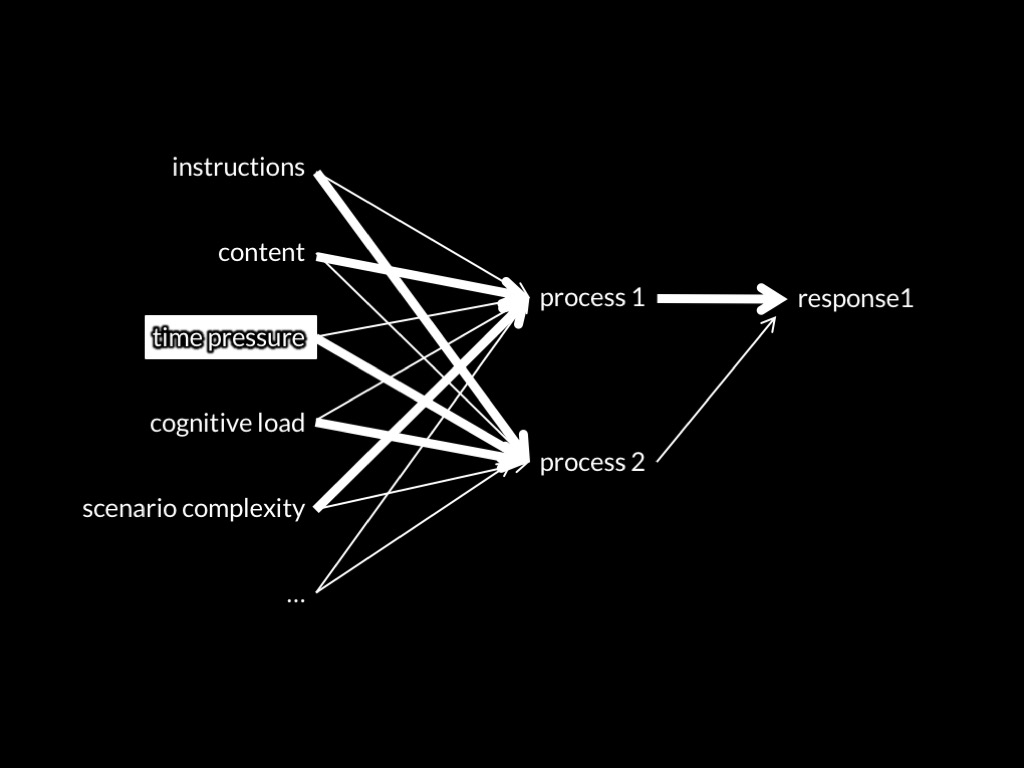

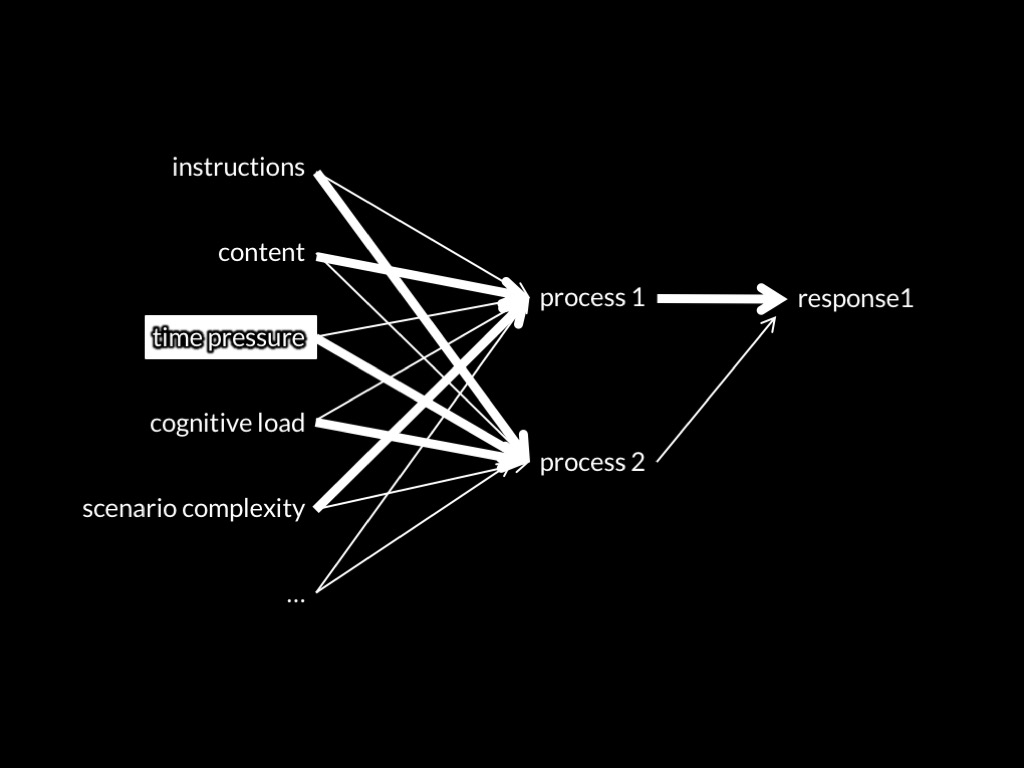

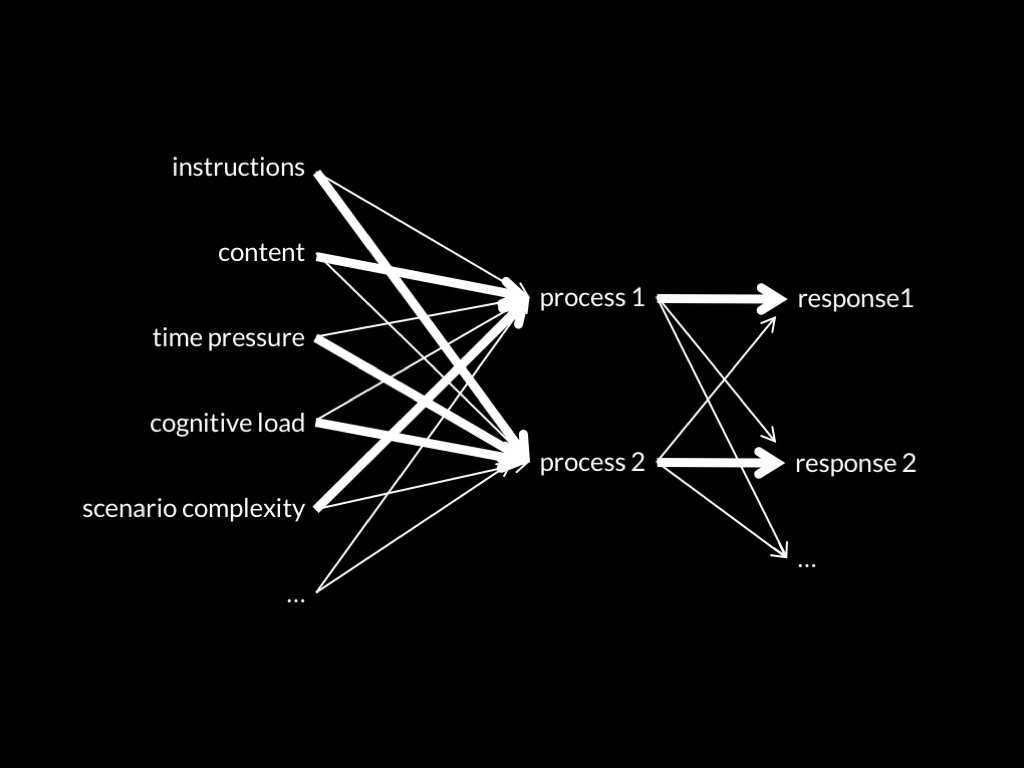

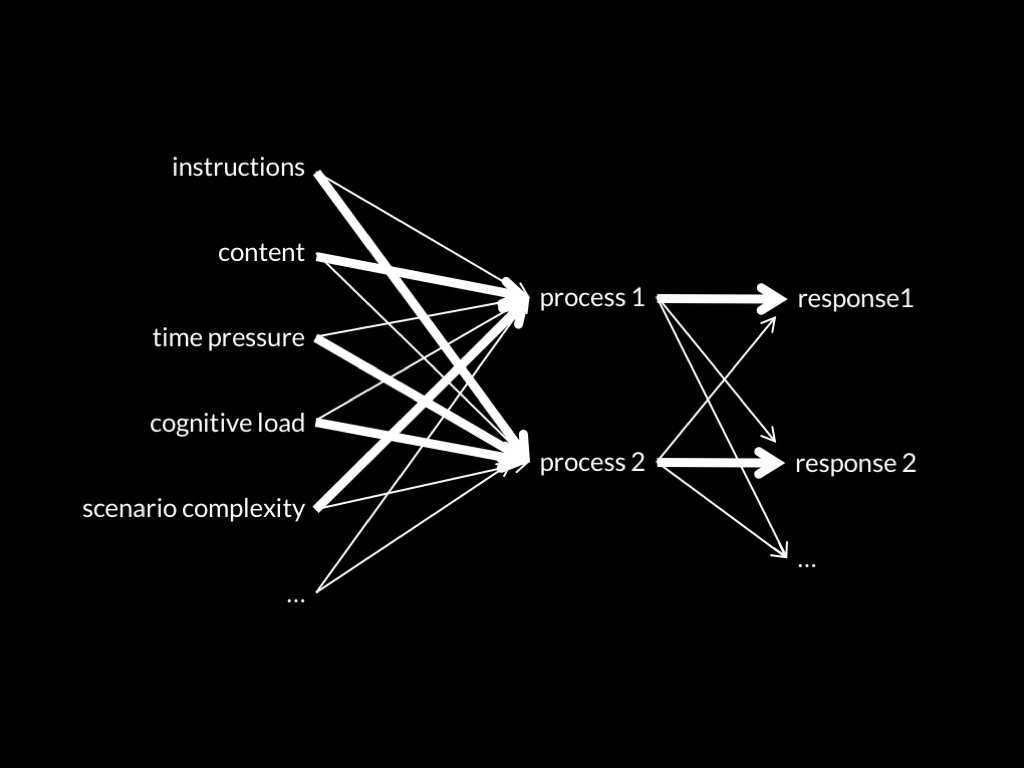

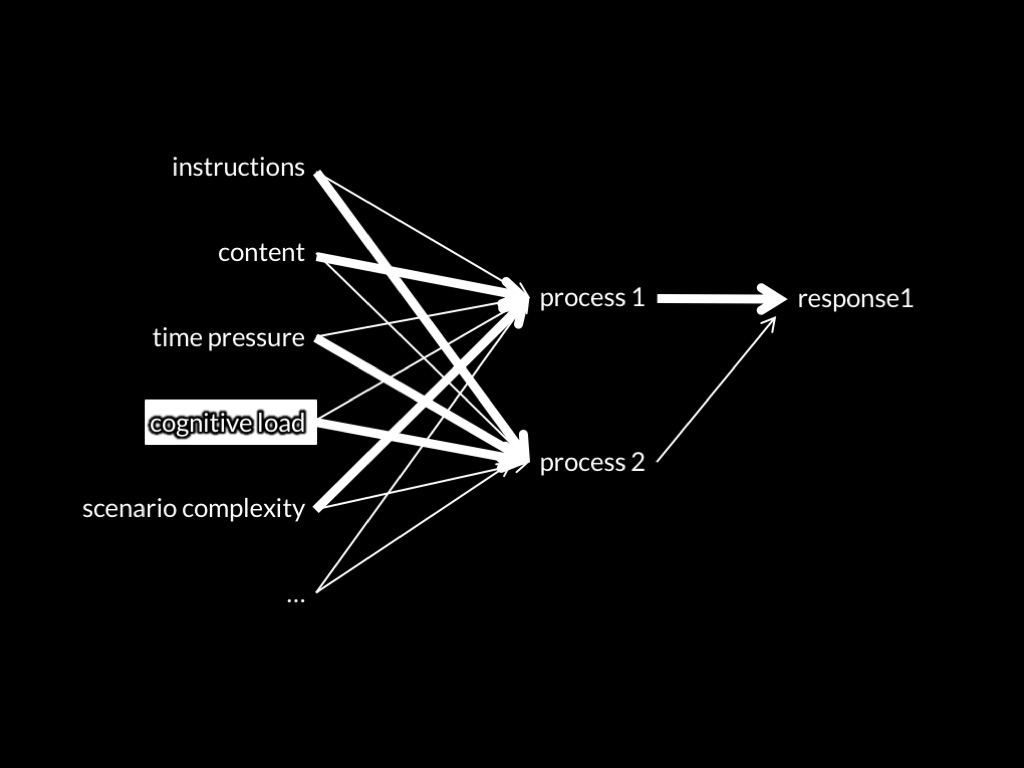

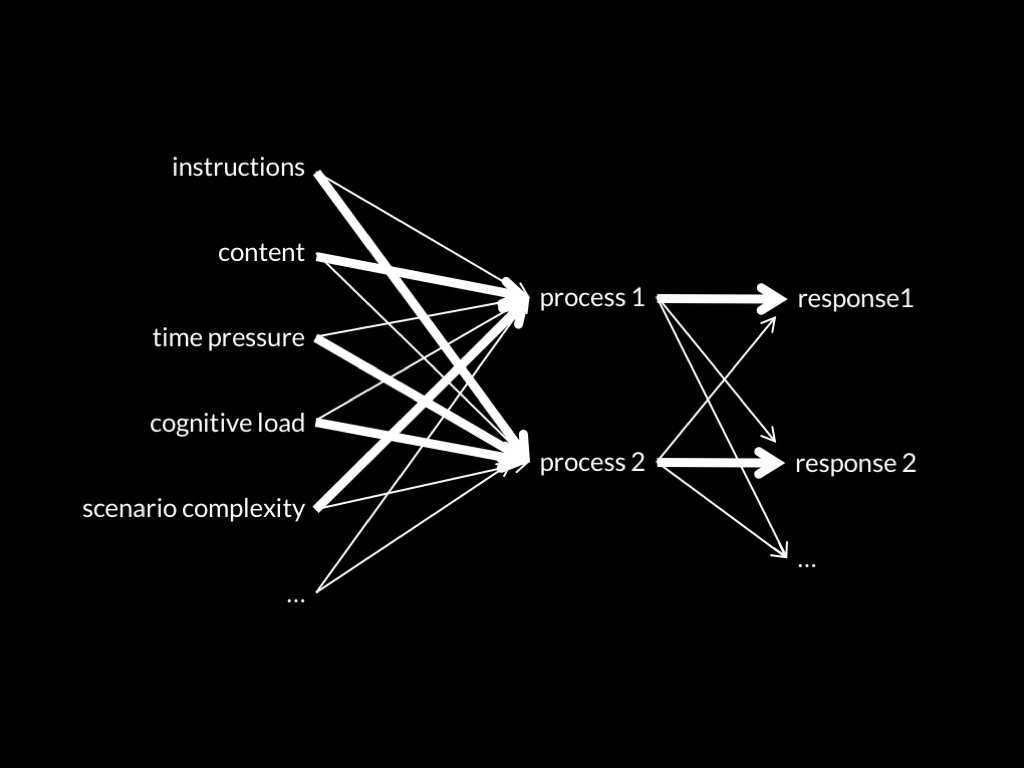

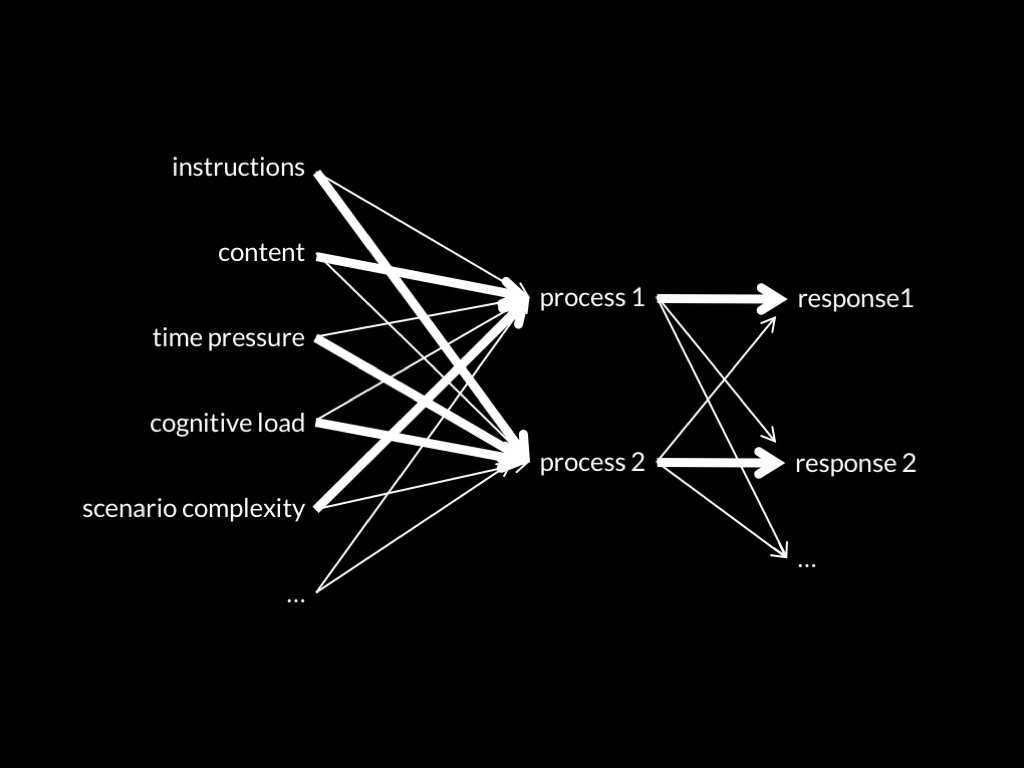

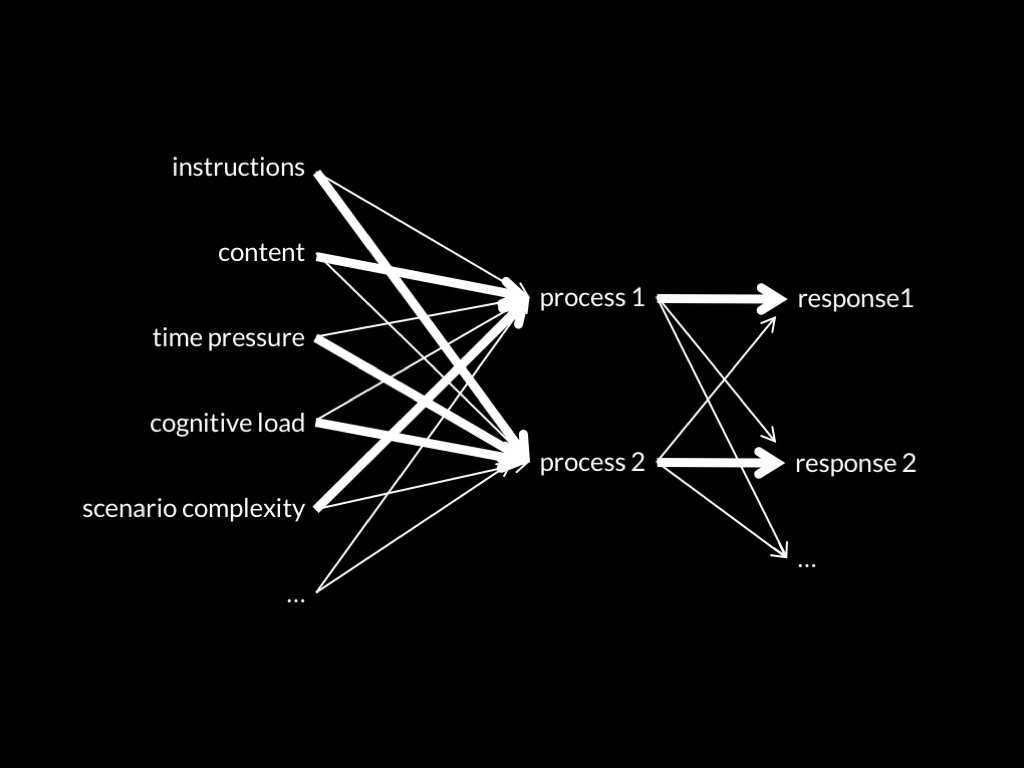

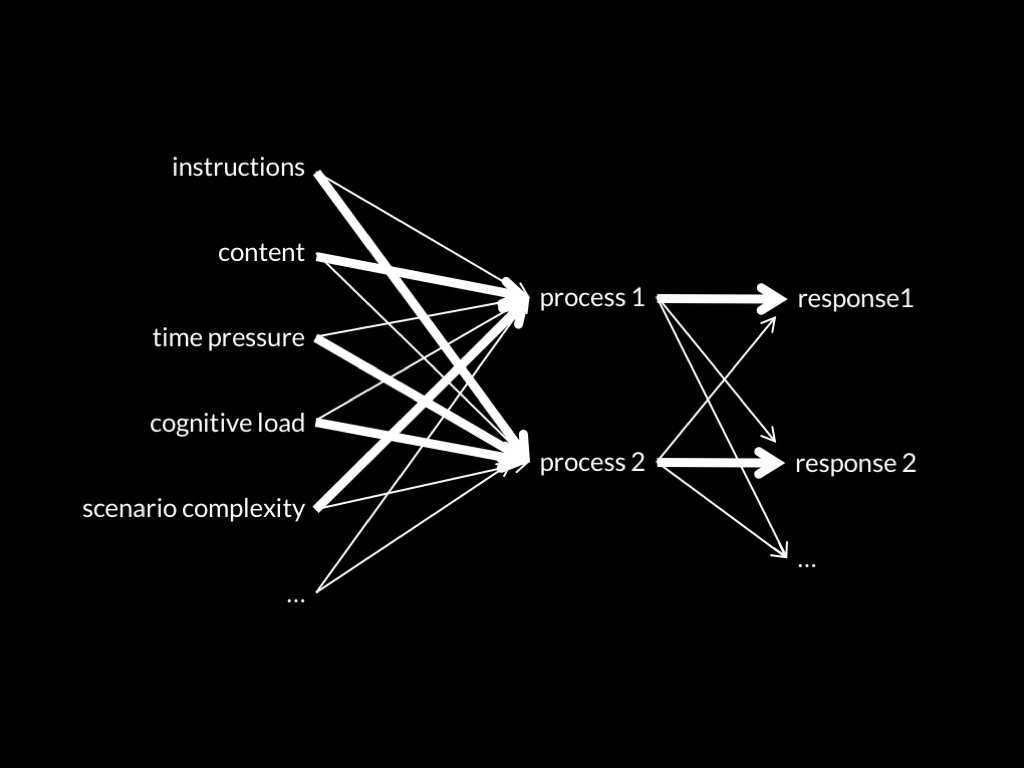

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

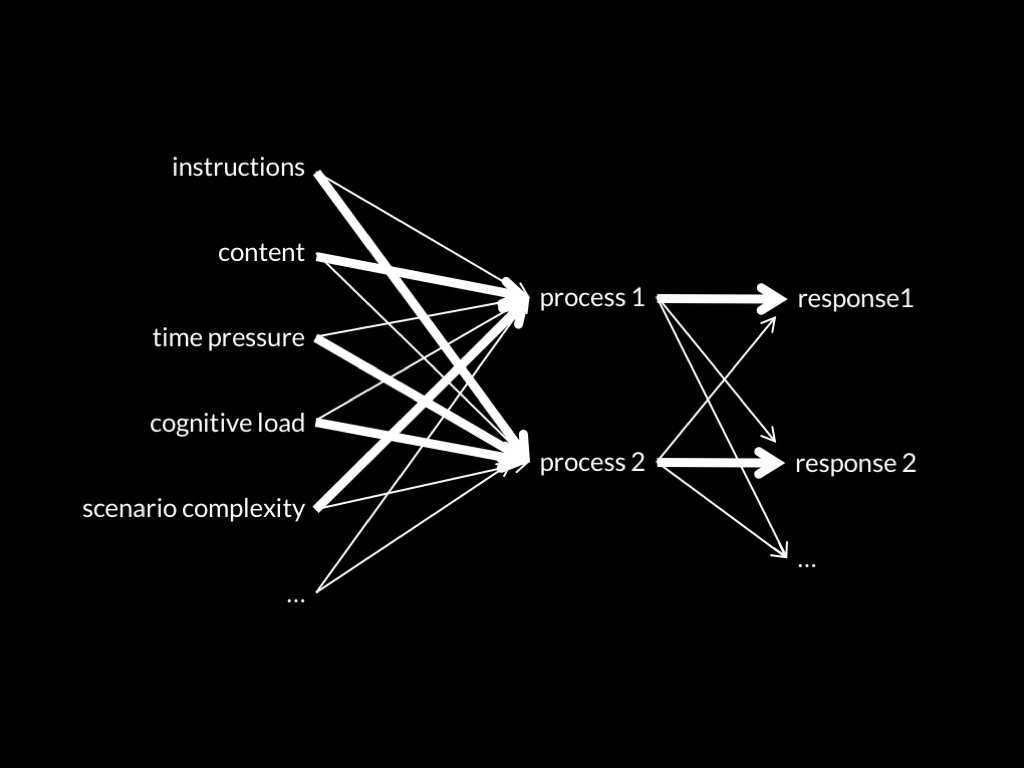

Why do we need auxiliary hypotheses?

Why do we need auxiliary hypotheses?

Compare physical cognition:

faster* processes :always characteristically Impetus (errors aside)

slower* processes : sometimes characteristically Newtonian

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

evidence for

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

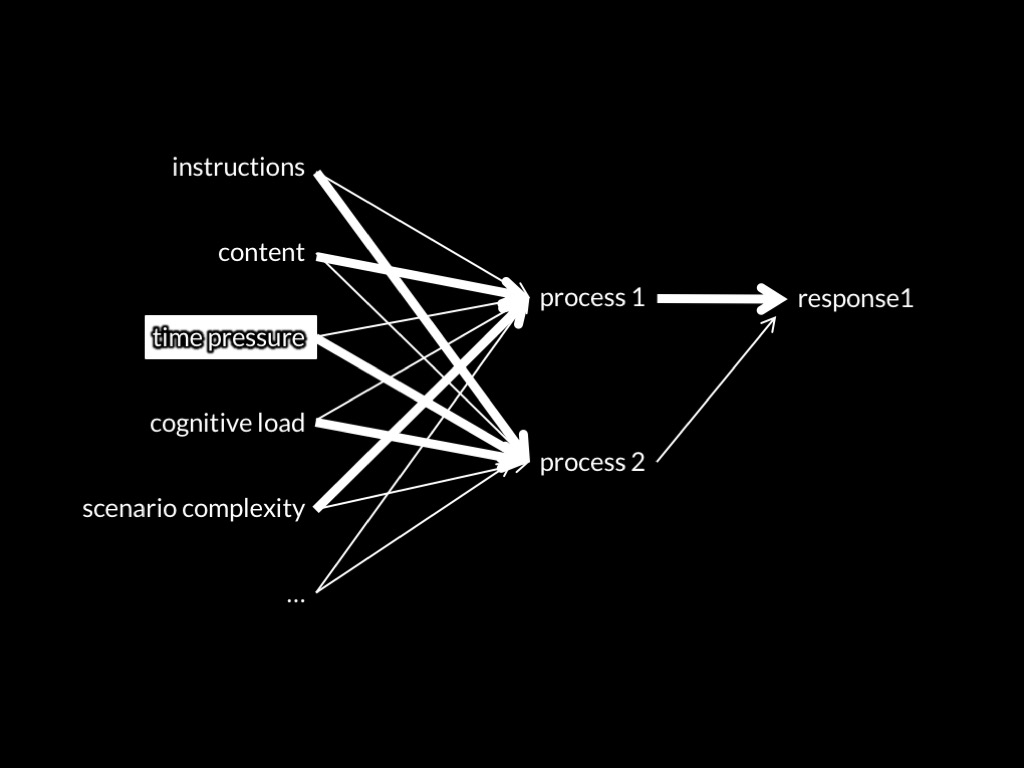

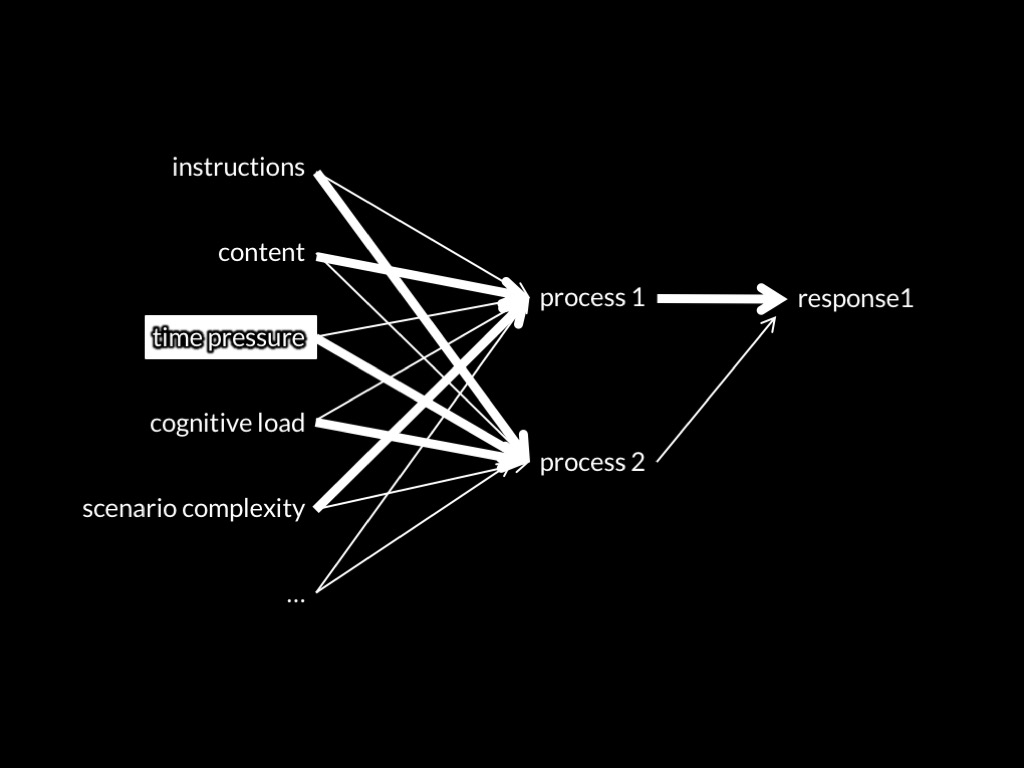

Prediction 1: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce characteristically consequentialist responses.

less time -> less influence of slow process

less influence of slow process -> less influence of more distal outcomes

less influence of more distal outcomes -> less consequentialist

‘low conflict’

‘Chidi is the driver of a trolley, whose brakes have just failed. [...] Chidi can turn the trolley, killing the one; or he can refrain from turning the trolley, killing the five’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 206).

May Chidi turn the trolley?

‘high conflict’

‘Eleanor can take the healthy specimen's parts, killing him, and install them in her [five] patients, saving them. Or he can refrain from taking the healthy specimen's parts, letting her [five] patients die’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 206).

May Eleanor kill the healthy person?

‘Frank is a passenger on a trolley whose driver has just shouted that the trolley's brakes have failed, and who then died of the shock. [...] Frank can turn the trolley, killing the one; or he can refrain from turning the trolley, letting the five die’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 207).

May Frank turn the trolley?

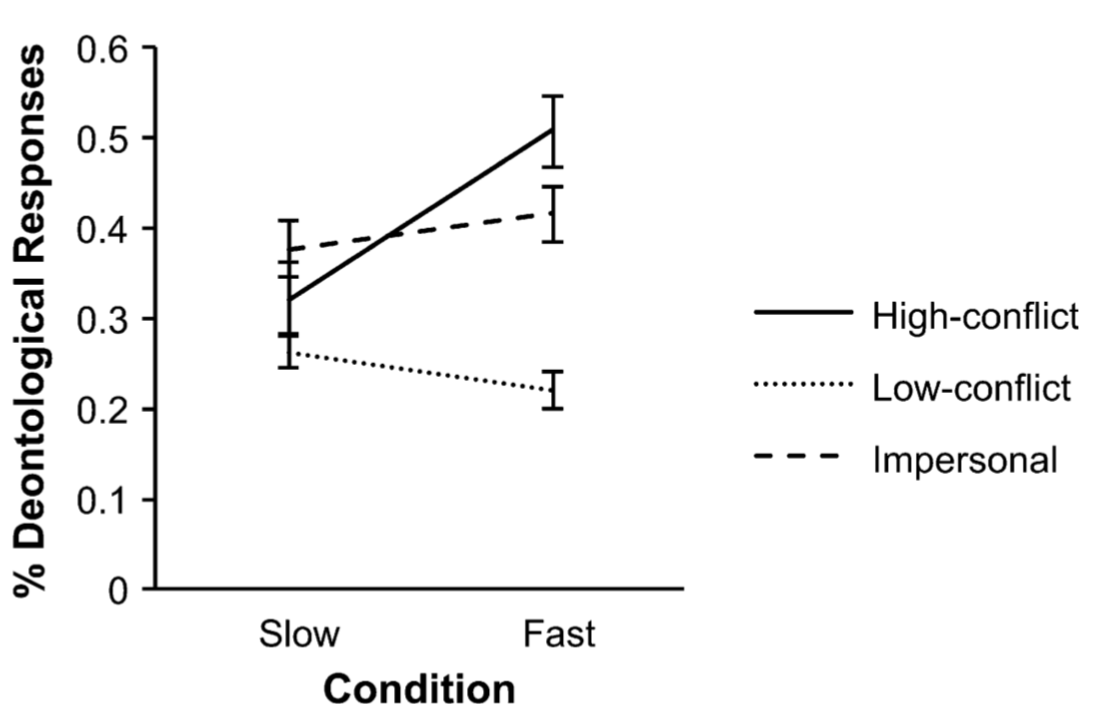

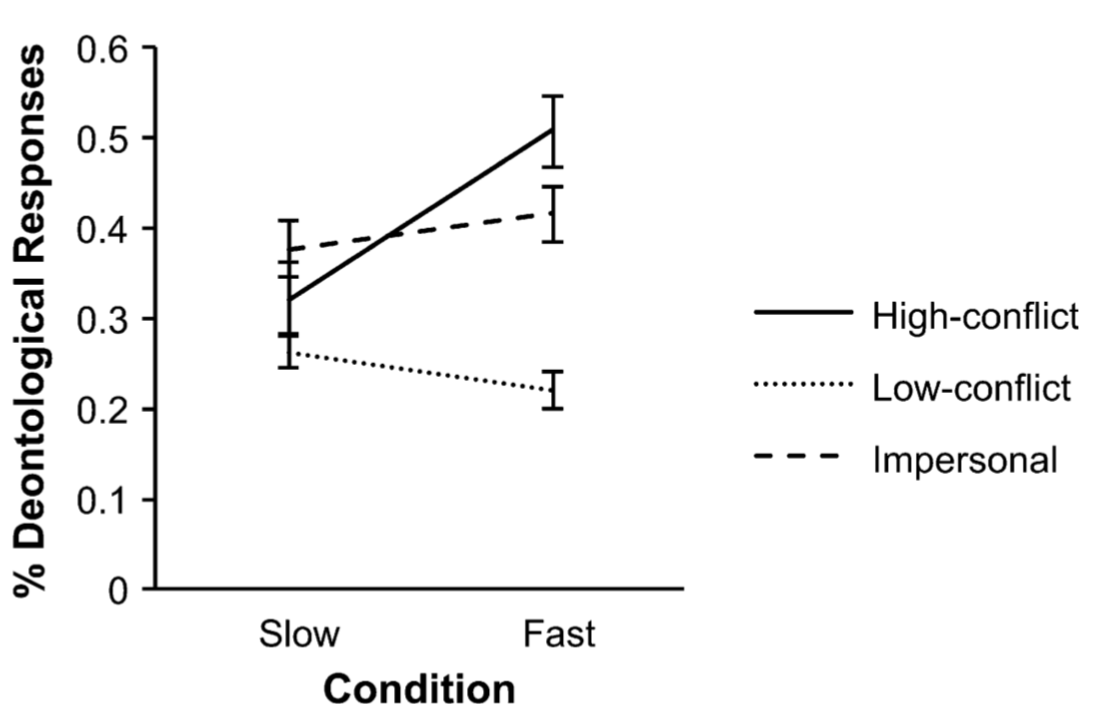

Suter & Hertwig, 2011 figure 1

‘participants in the time-pressure condition, relative to the no-time-pressure condition, were more likely to give ‘‘no’’ responses in high-conflict dilemmas’

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Prediction 1: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce characteristically consequentialist responses.

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Prediction 1: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce consequentialist responses.

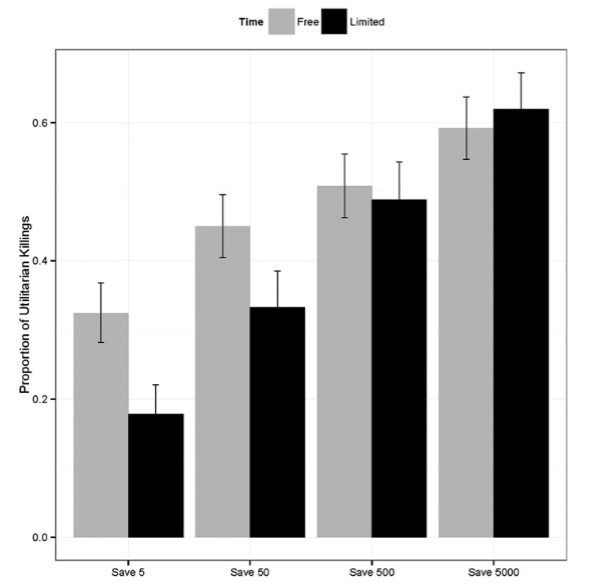

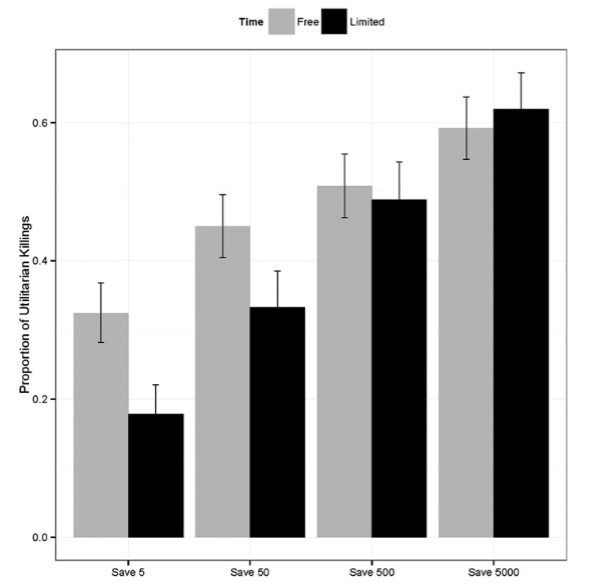

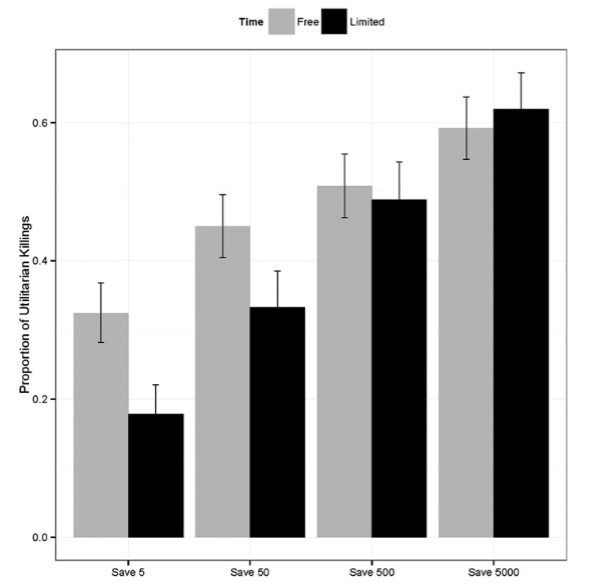

Trémolière and Bonnefon, 2014 figure 4

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Prediction 1: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce consequentialist responses.

Prediction 2*: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce sensitivity to outcomes.

Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014, p. figure 4)

Prediction 2*: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce sensitivity to outcomes.

Gawronski & Beer (2017, p. figure 1); data from Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

Prediction 2*: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce sensitivity to outcomes.

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

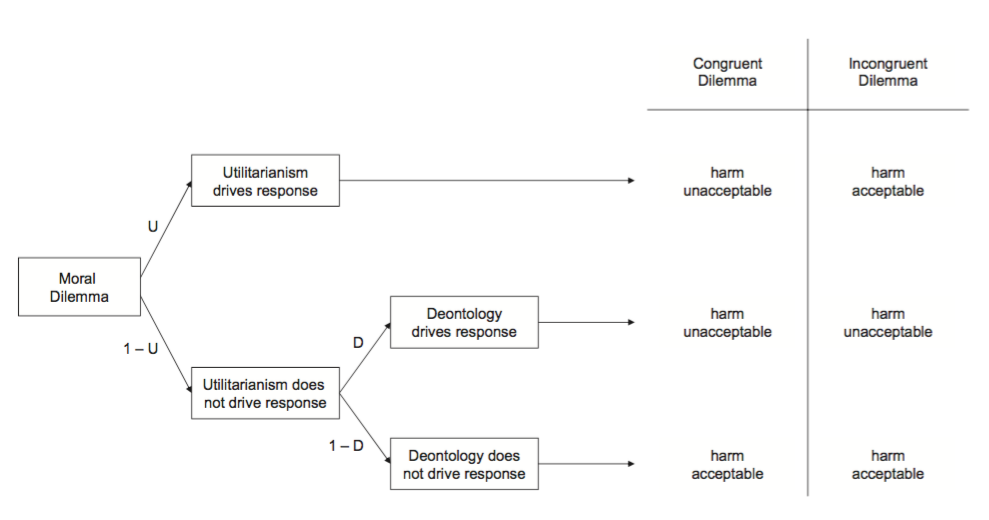

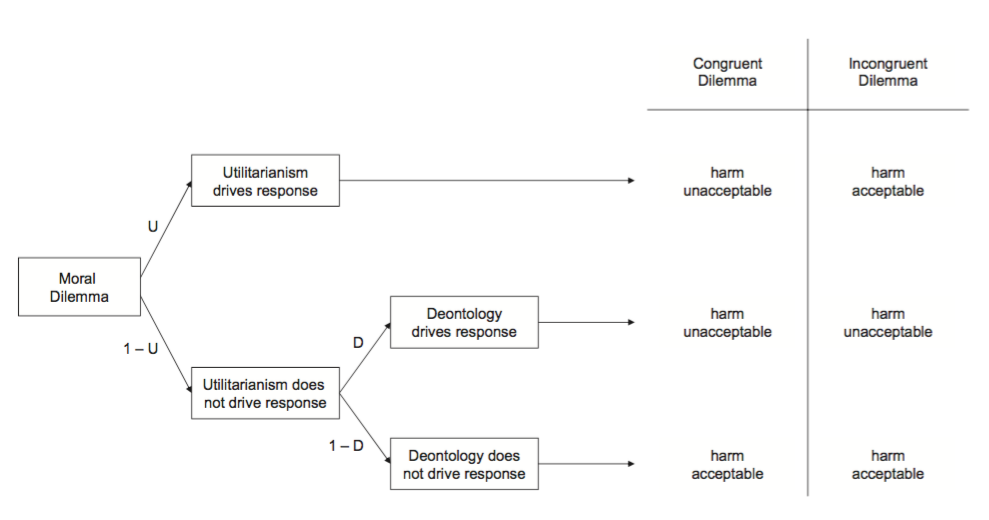

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

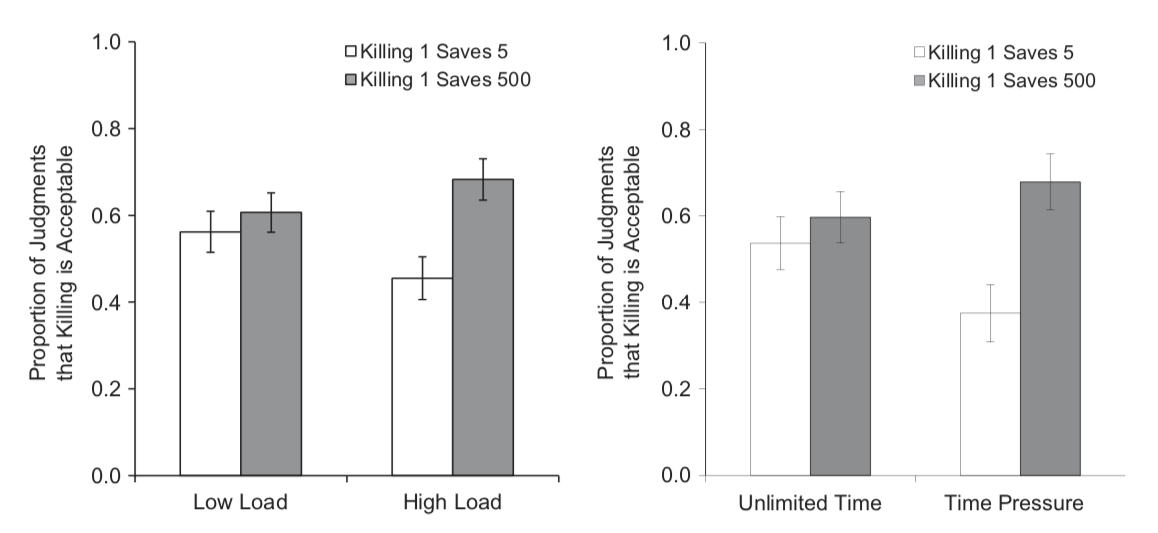

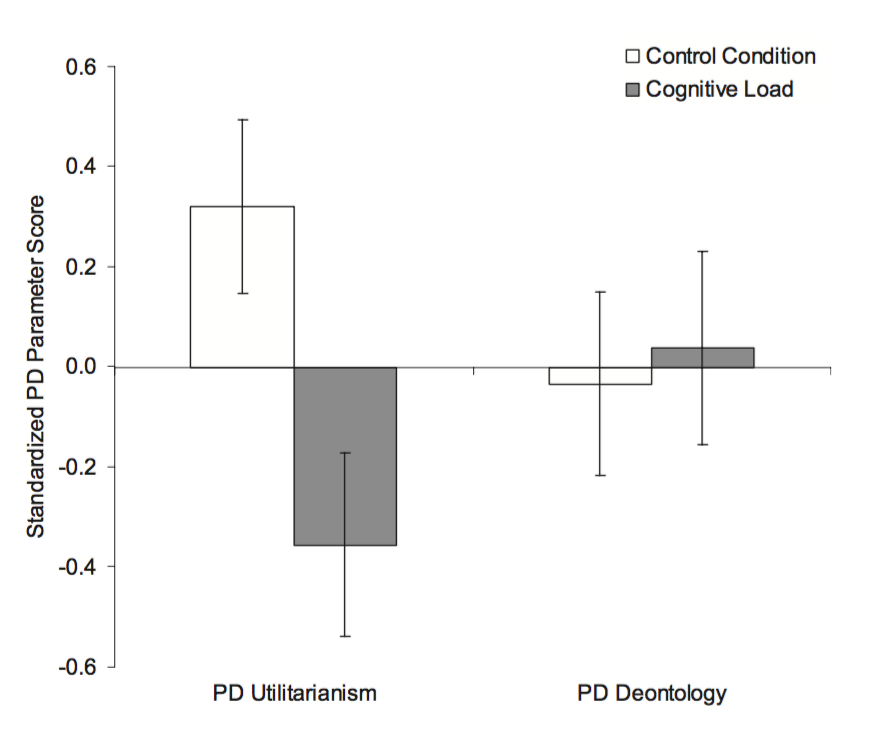

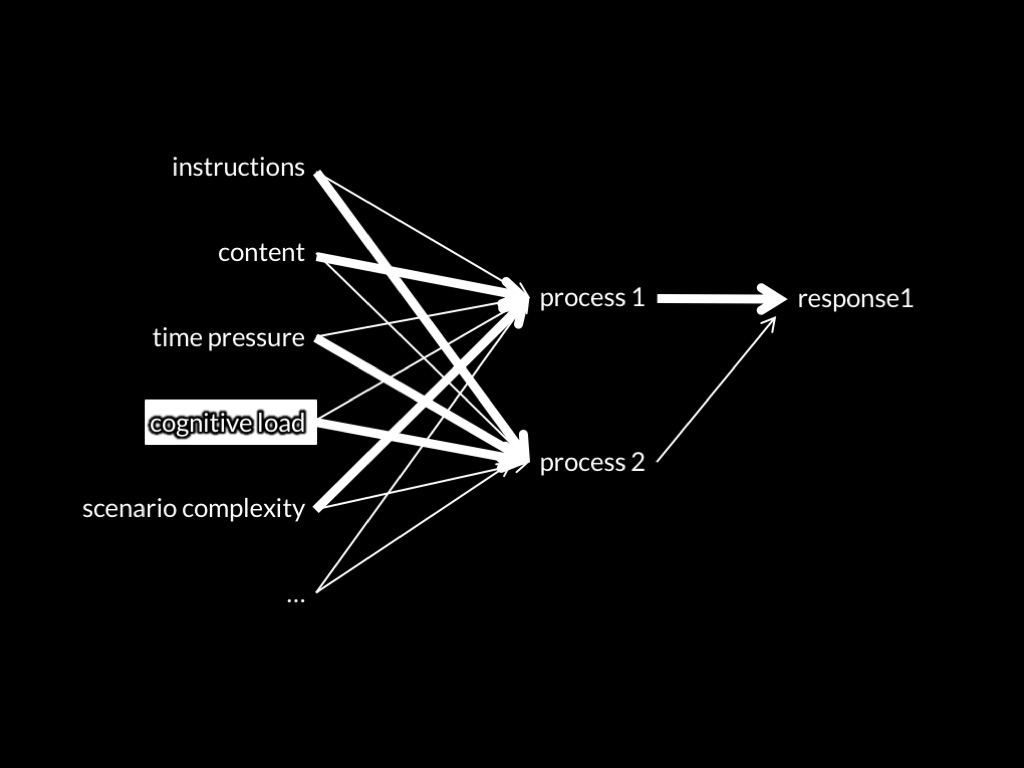

Prediction 3: higher cognitive load will reduce the dominance of the more outcome-sensitive process.

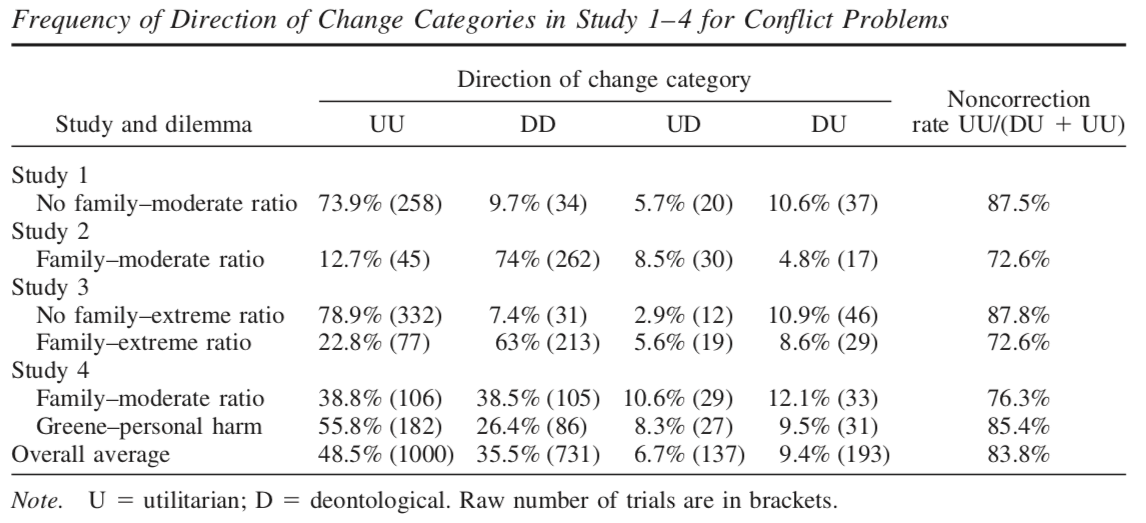

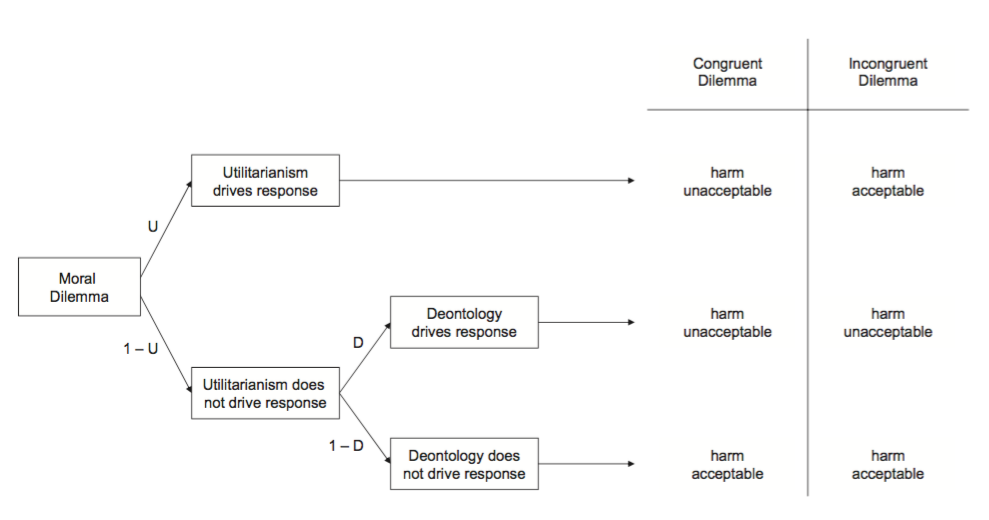

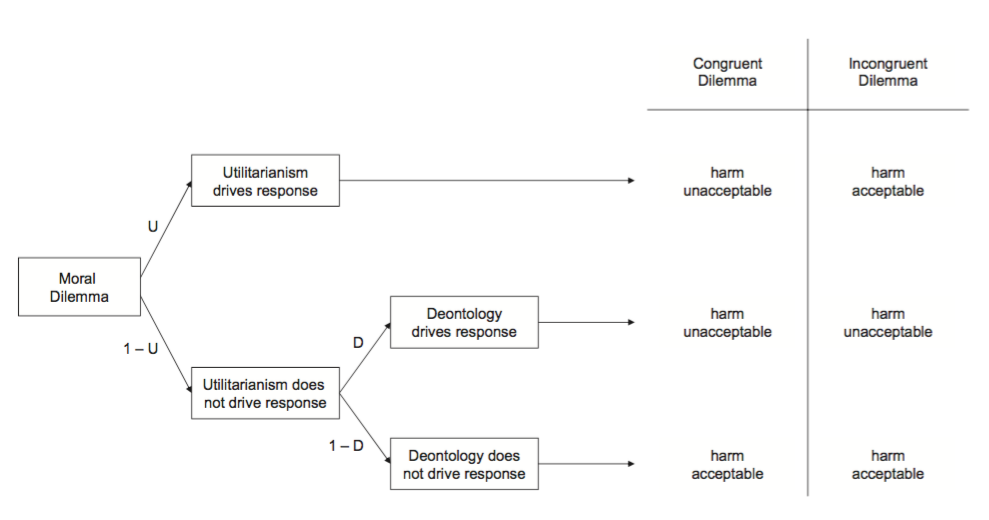

Conway & Gawronsky 2013, figure 1

Conway & Gawronsky 2013, figure 3

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Prediction 3: higher cognitive load will reduce the dominance of the more outcome-sensitive process.

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

appendix

evaluating the evidence

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

‘Submarine (4/60)

You are responsible for the mission of a submarine [...] leading [...] from a control center on the beach. An onboard explosion has [...] collapsed the only access corridor between the upper and lower levels of the ship. [...] water is quickly approaching to the upper level of the ship. If nothing is done, 12 [extreme:60] people in the upper level will be killed.

[...] the only way to save these people is to hit a switch in which case the path of the water to the upper level will be blocked and it will enter the lower level of the submarine instead.

However, you realize that your brother and 3 other people are trapped in the lower level. If you hit the switch, your brother along with the 3 other people in the lower level (who otherwise would survive) will die [...]

Would you hit the switch?’

Bago & de Neys, 2019 supplementary materials

first response under time pressure and cognitive load

second response under neither

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

prediction: first response will be less influenced by outcomes than the second

Bago & de Neys, 2019 table 2

‘Our critical finding is that although there were some instances in which deliberate correction occurred, these were the exception rather than the rule. Across the studies, results consistently showed that in the vast majority of cases in which people opt for a [consequentialist] response after deliberation, the [consequentialist] response is already given in the initial phase’

Bago & de Neys, 2019 p. 1794

Objection: consistency effects? No!

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Suter & Hertwig, 2011 : yes

Bago & de Neys, 2019 : no

Suter & Hertwig, 2011 figure 1

‘participants in the time-pressure condition, relative to the no-time-pressure condition, were more likely to give ‘‘no’’ responses in high-conflict dilemmas’

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the outcomes of an action

Suter & Hertwig, 2011 : yes

Bago & de Neys, 2019 : no

Neither study observed the effects of manipulating outcomes

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

Conway & Gawronsky 2013, figure 1

Maybe people just prefer not to act when under time pressure?

Conway & Gawronsky 2013, figure 1

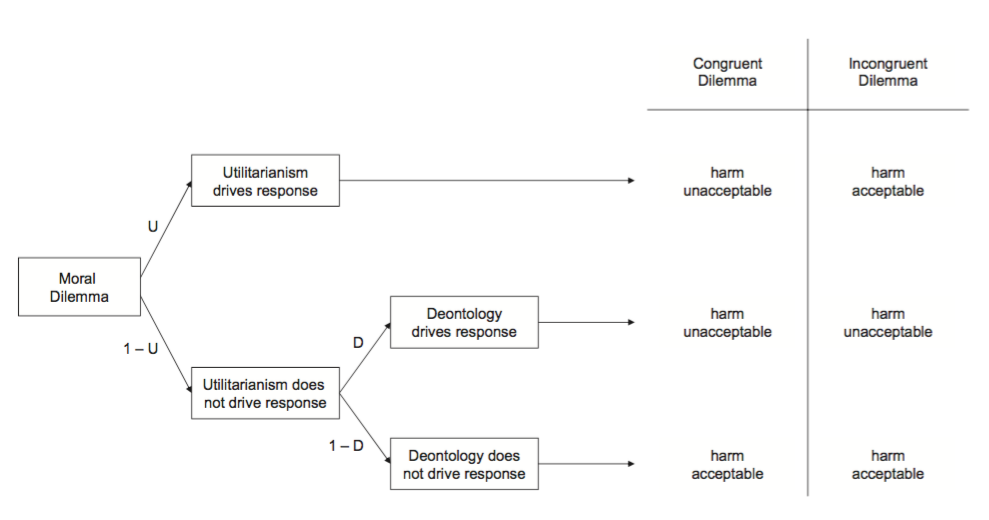

Gawronski et al, 2017 figure 1

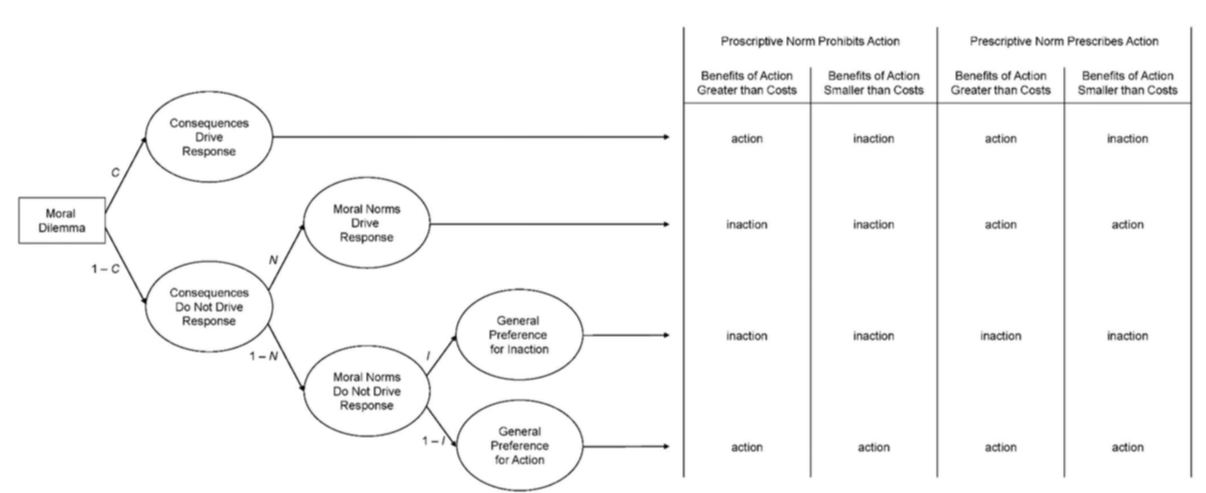

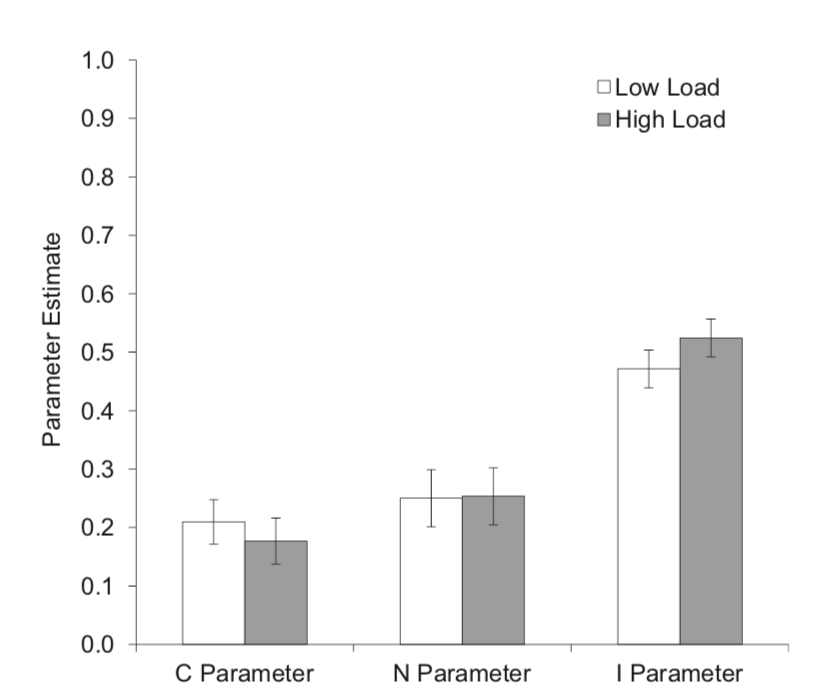

Gawronski et al, 2017 figure 4

‘The only significant effect in these studies was a significant increase in participants’ general preference for inaction as a result of cognitive load. Cognitive load did not affect participants’ sensitivity to morally relevant consequences’

‘cognitive load influences moral dilemma judgments by enhancing the omission bias, not by reducing sensitivity to consequences in a utilitarian sense’

‘Instead of reducing participants’ sensitivity to consequences in a utilitarian sense, cognitive load increased participants’ general preference for inaction. ’

Gawronski et al, 2017 p. 363

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

Suter & Hertwig, 2011 : yes

Bago & de Neys, 2019 : no

Gawronski et al, 2017 : no

Can we resolve the apparent contradiction by preference for inaction under time-pressure?

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

aux. hypothesis: only the slow process ever flexibly and rapidly takes into account differences in the more distal outcomes of an action

reflective equilibrium